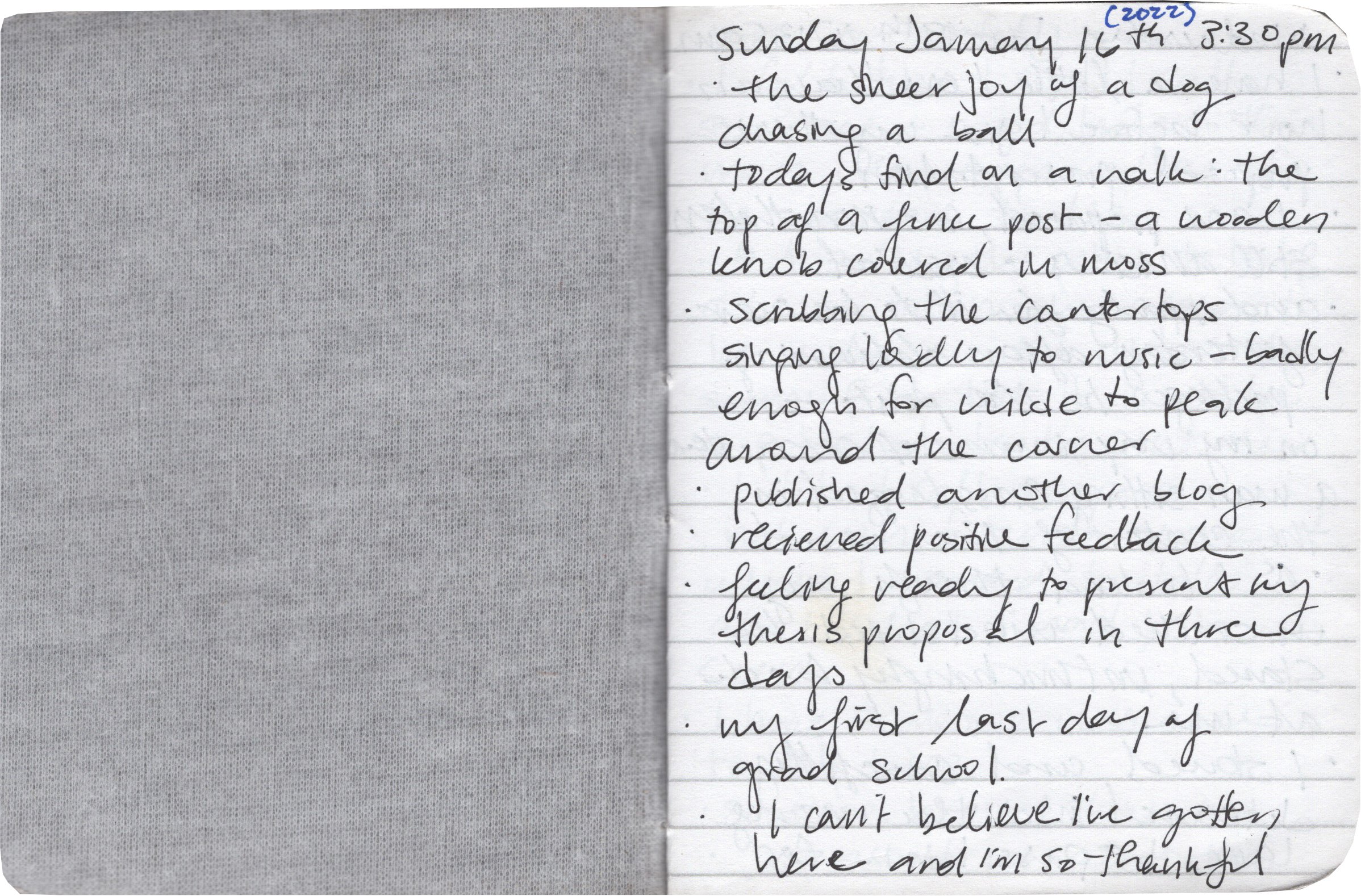

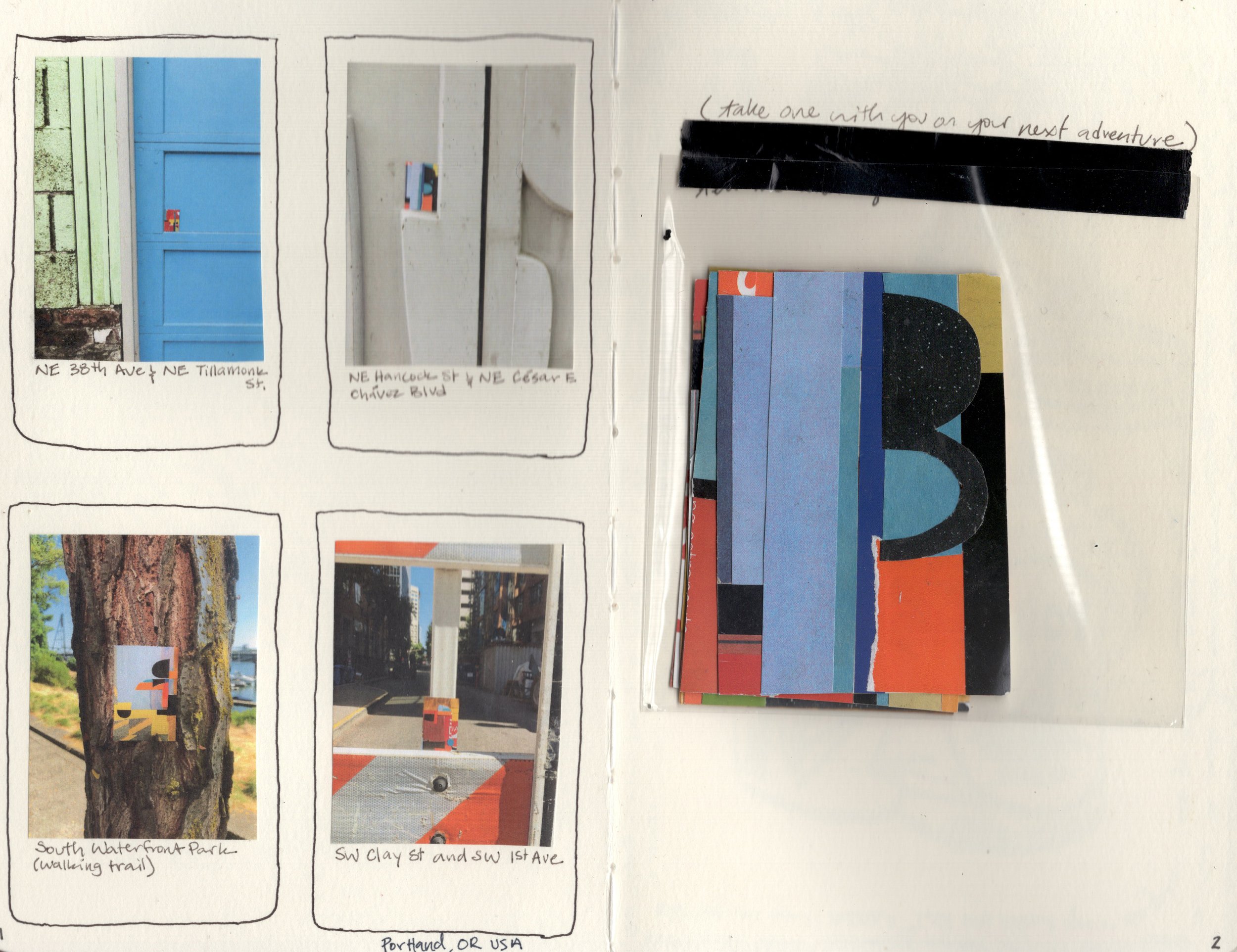

For the last two years I’ve been collecting answers to the question: what can be both small and big simultaneously? This field research routinely occurred during my daily dog walks around my neighborhood.

My dog, Mr. Wilde and I would walk past the house on the corner with its mini-me replica that also sits in the corner of the corner lot. This maquette reminds me of Jorie Garcia’s Miniature Big Pink project I’ve been following.

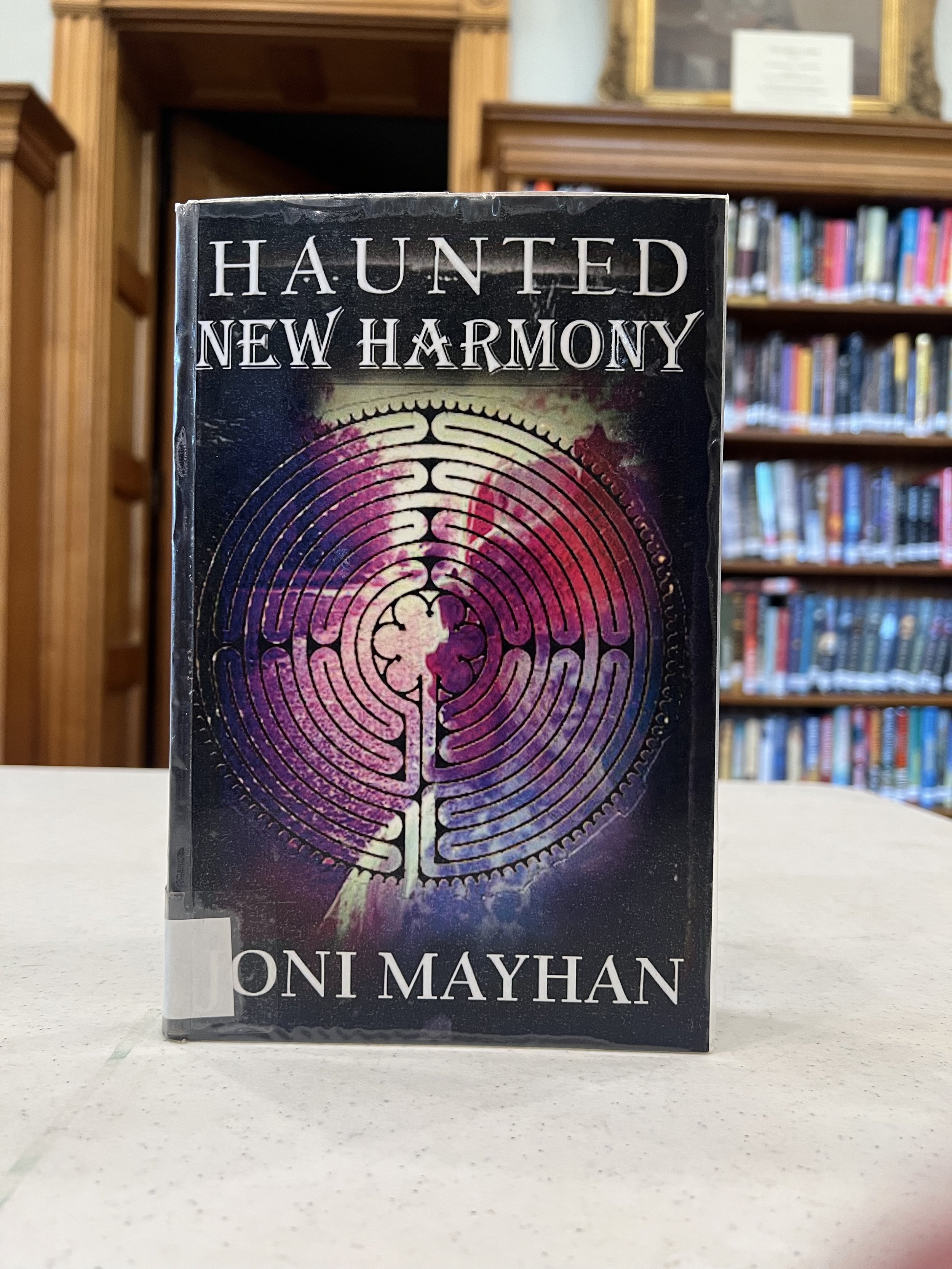

Cheering from afar, I was excited to see that her custom designer dollhouse won first place in the Oregon State Fair this past summer. Jorie’s project inspires me to imagine all the potential interiors for this small big, easy to miss, (likely haunted) model house that resides in my neighborhood.

Located throughout my neighborhood in NE Portland is a loop of small but many libraries filled with books, flowers, art, sticks, dog treats, dvd movies, yarn and more. Among these finds, I discovered a map that locates more small big sidewalk installations throughout Portland, and beyond.

But mostly, Wilde leads our walks, motivated by the locations of all the best snacks.

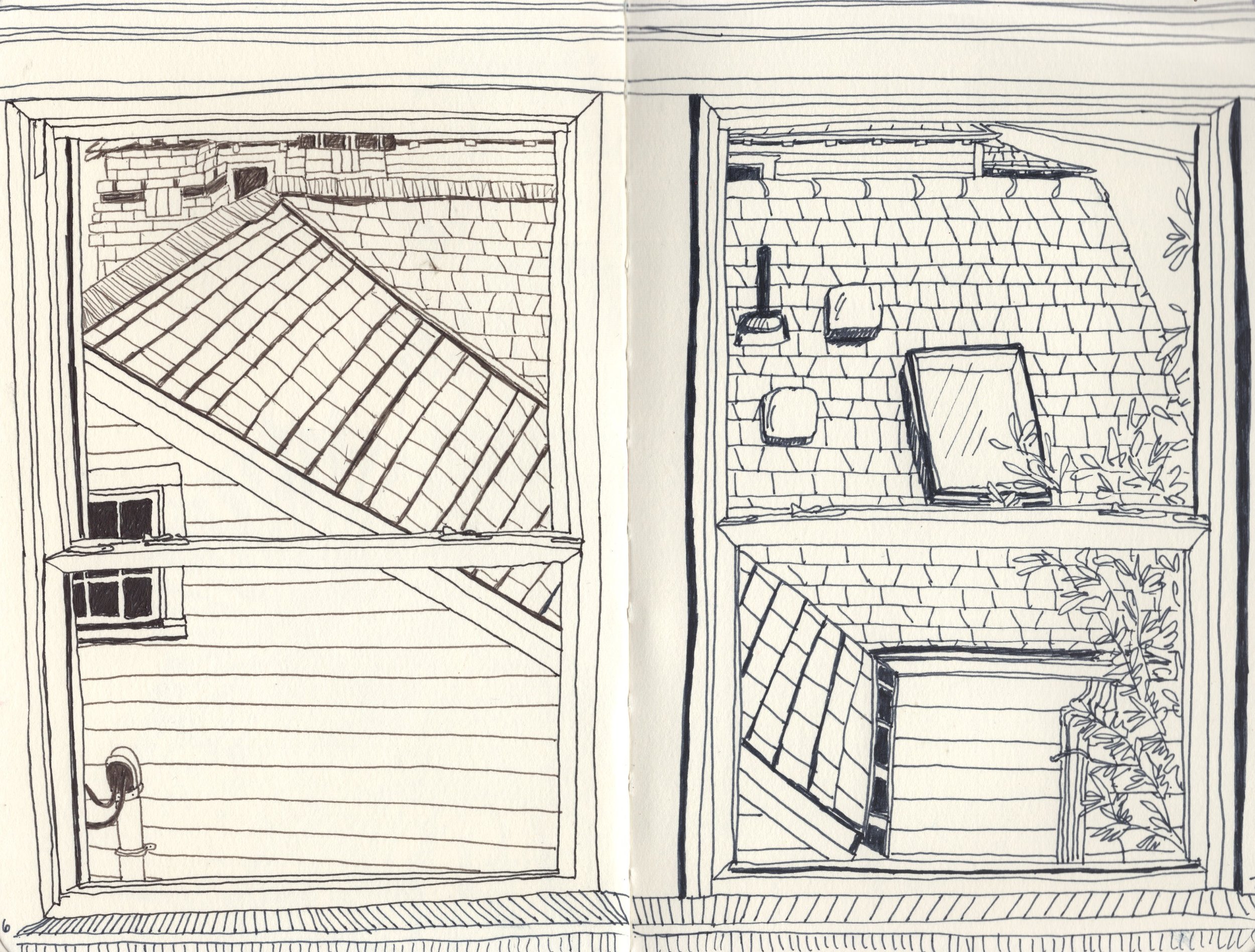

The treats I find, when I look closely, are the mini turtle notes scribbled on rocks, or the many wishes tied to trees.

Some days there is poetry written across balloons bouncing in the wind, making the words of Jack Gilbert dance and twist. On the rainy days, the words smear and run like mascara when I cry, until eventually they deflate altogether.

On certain streets and times of year, you can see the warning sign for the tiger cave or the poster pleading, “We like it here. Please don’t take us. We are log,” or “Wanted: brains - all sizes, all ages, smart and not smart.”

Sometimes, the sign is as simple as a one-word, power-washed reminder punctuated by a smiley face.

The poetry posts remind me to keep going and give instructions for not giving up.

These small big moments of pause remind me to notice the light in spring, quiet raindrops, that everything is music and the comfort of wood.

I read the words:

I want a word that means

okay and not okay,

a word that means

devastated and stunned with joy.

I want the word that says

I feel it all, all at once.

The beginning of Rosemerry Trommer’s poem, For When People Ask hits me in my gut. I desperately want that word too.

It was two years ago that my proposal to exhibit a show about language at Eastern Oregon University’s Nightingale Gallery was accepted. I went from having all the right words (or enough for them to tell me yes to my first solo show in over five years), to having no words at all. I was surprised to find that I no longer knew what to say.

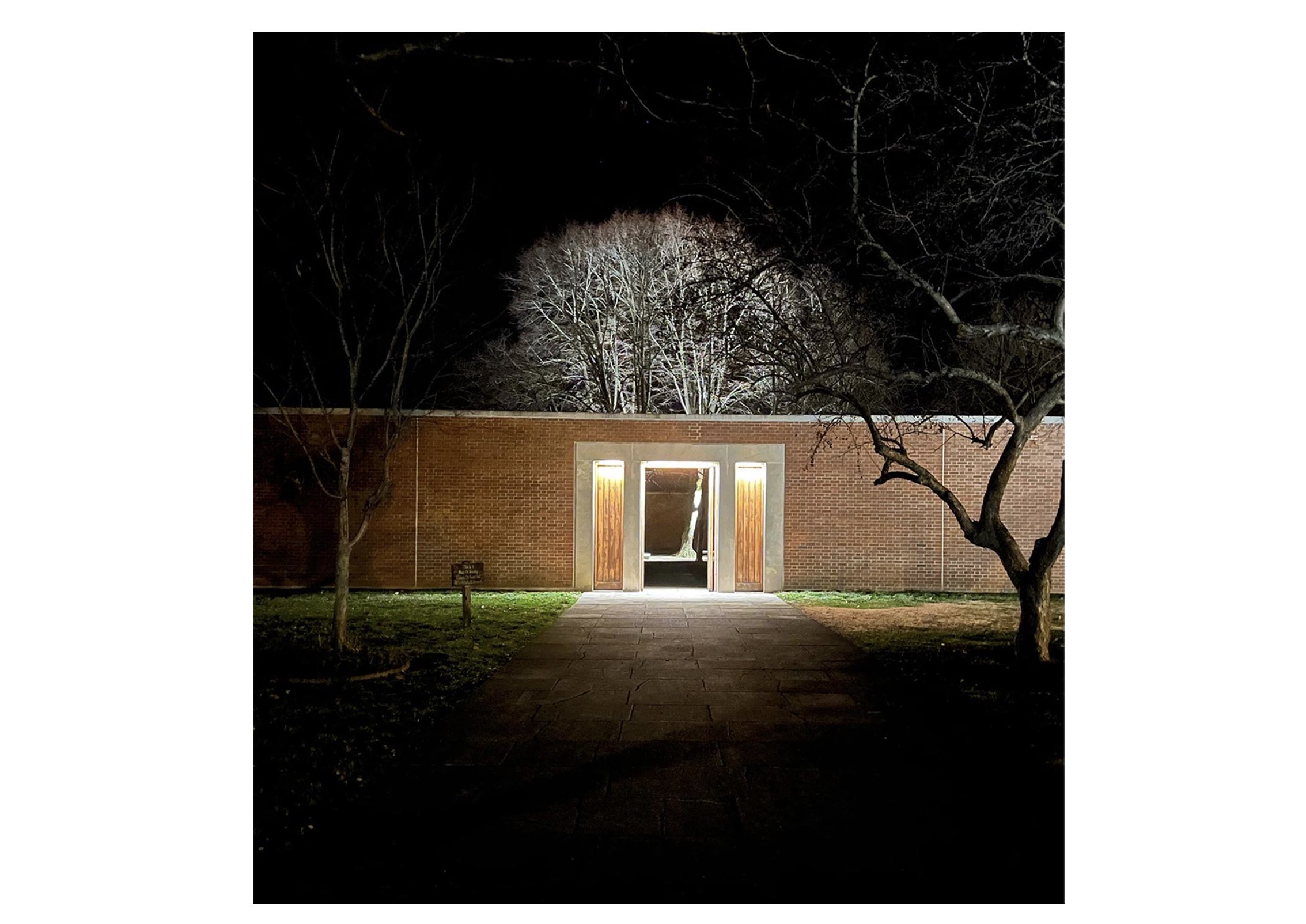

Nightingale Gallery is located in the small city of La Grande, OR, whose namesake is a comment on the area’s abundant beauty and location in the Grande Ronde Valley.

Walking my dog and collecting these observations, a series of small big things, reminded me to practice what I tell students in workshops: start where you are.

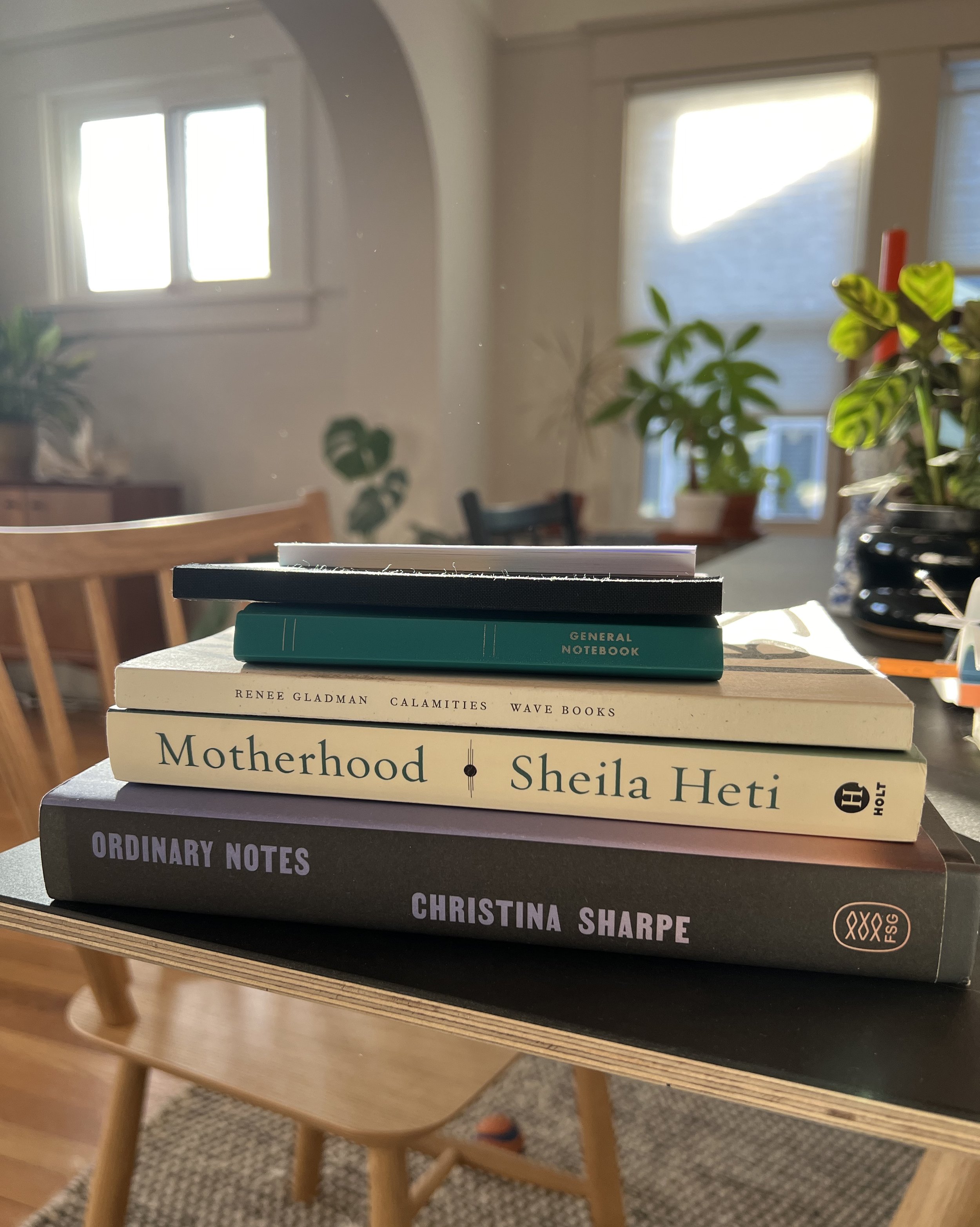

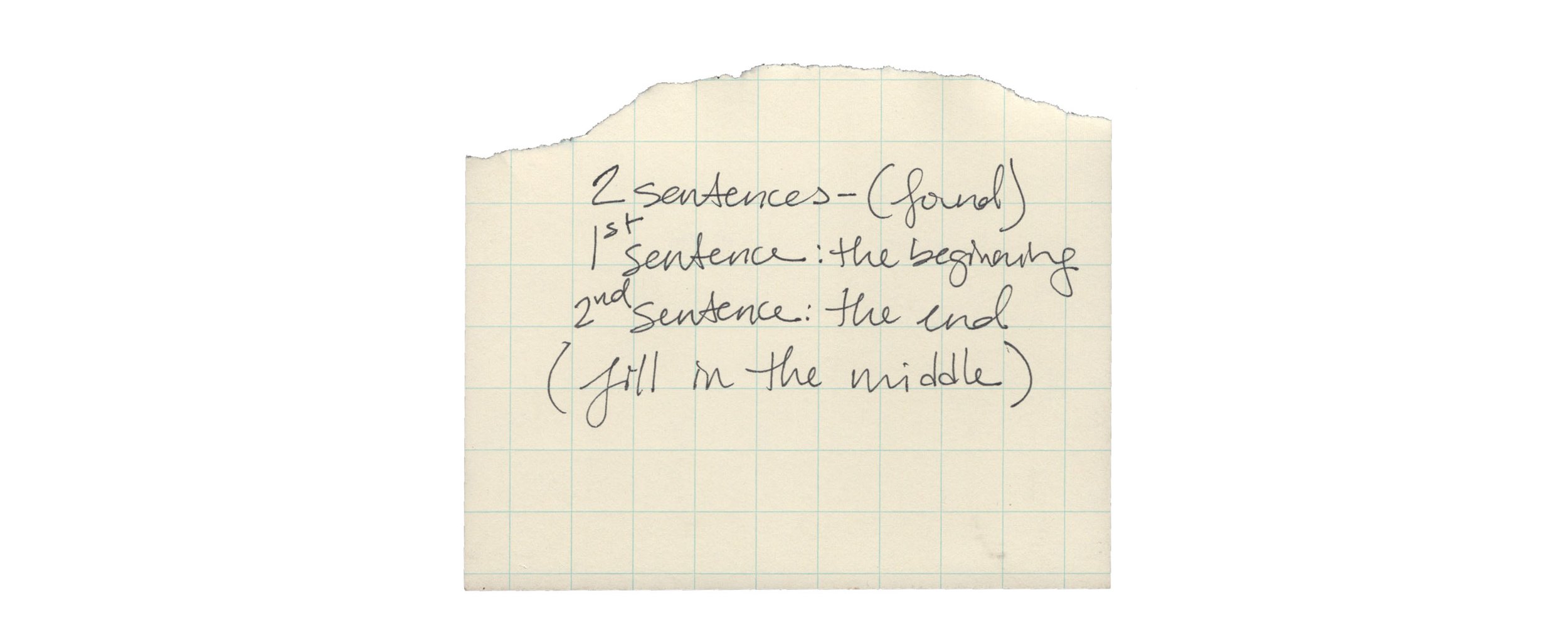

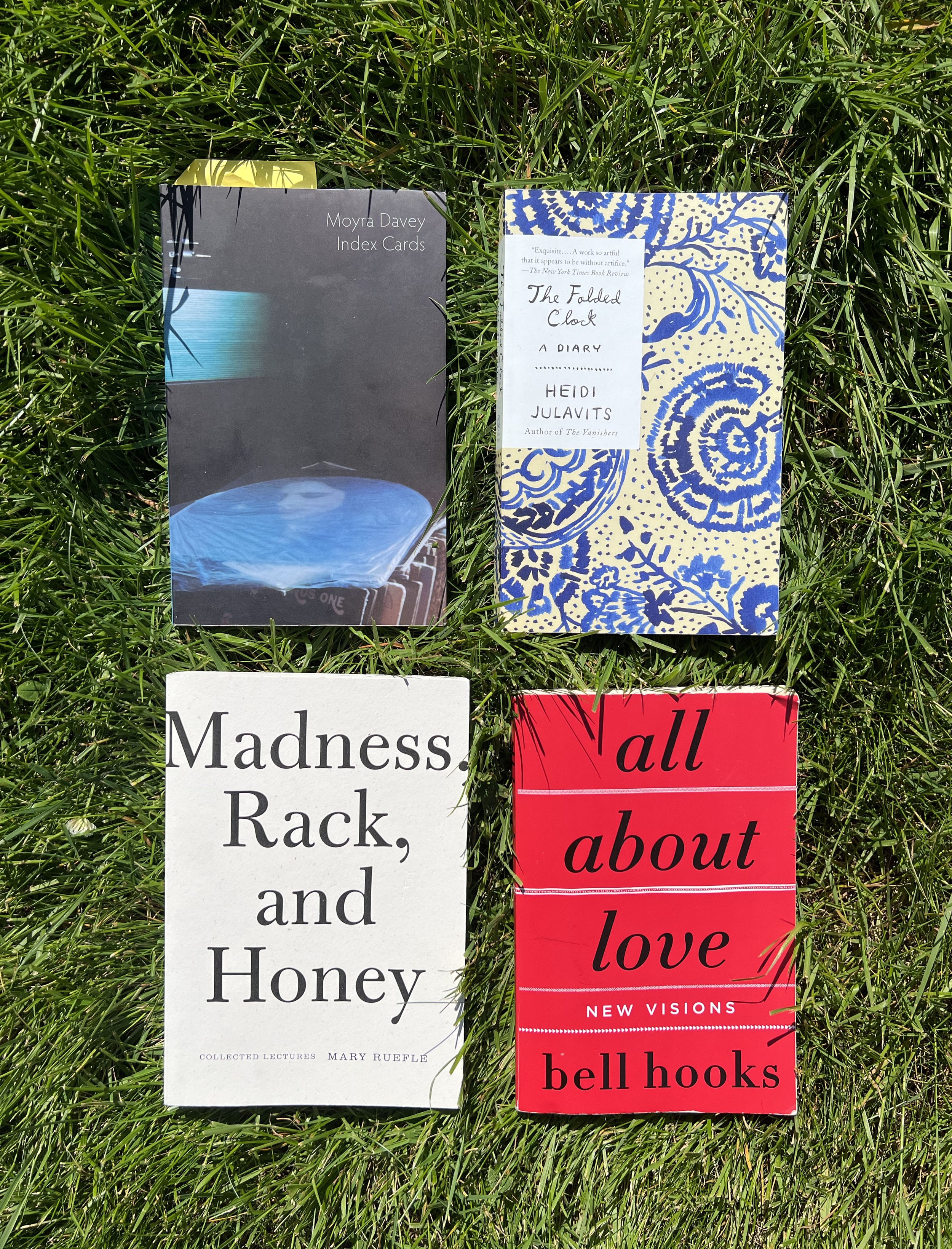

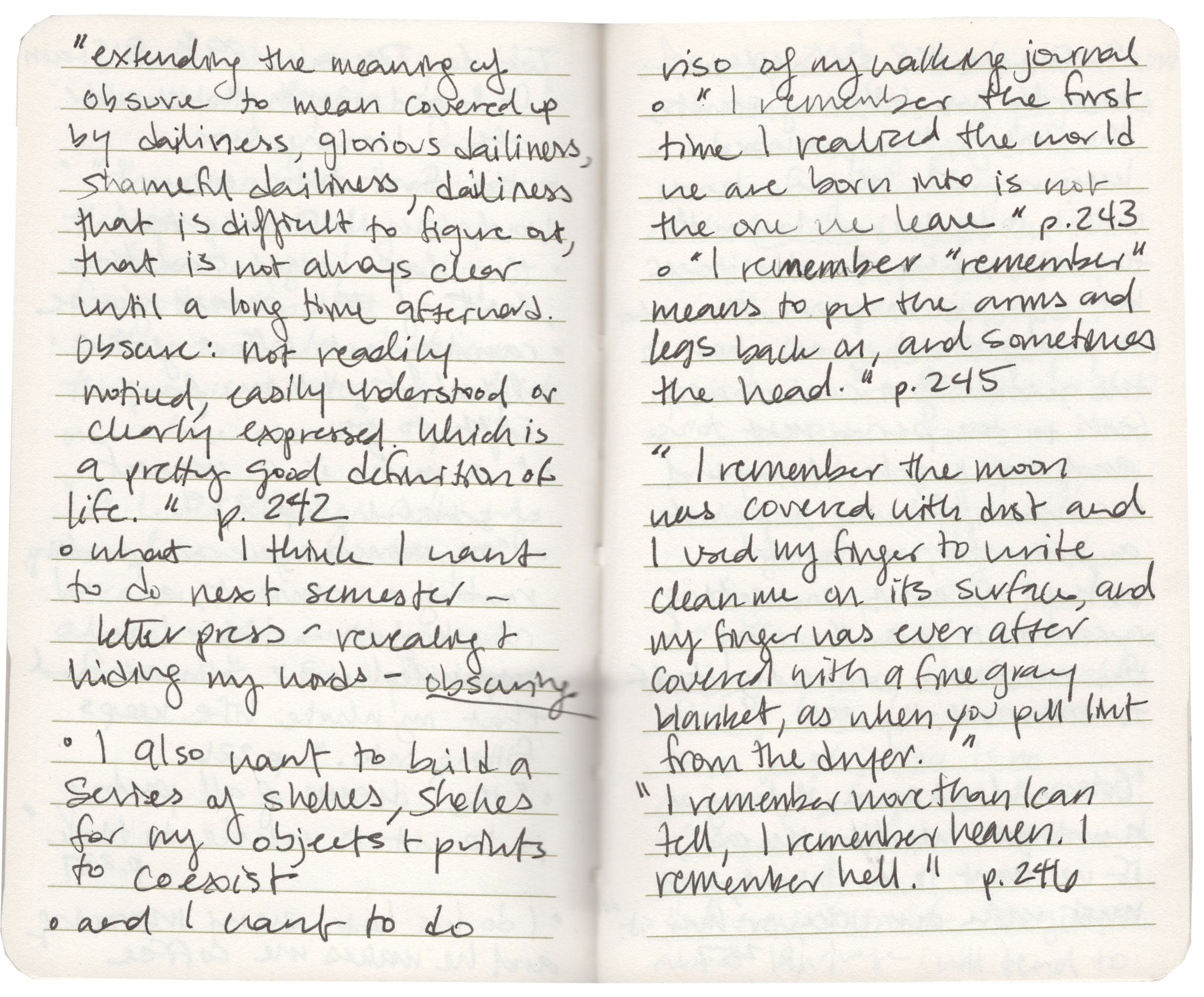

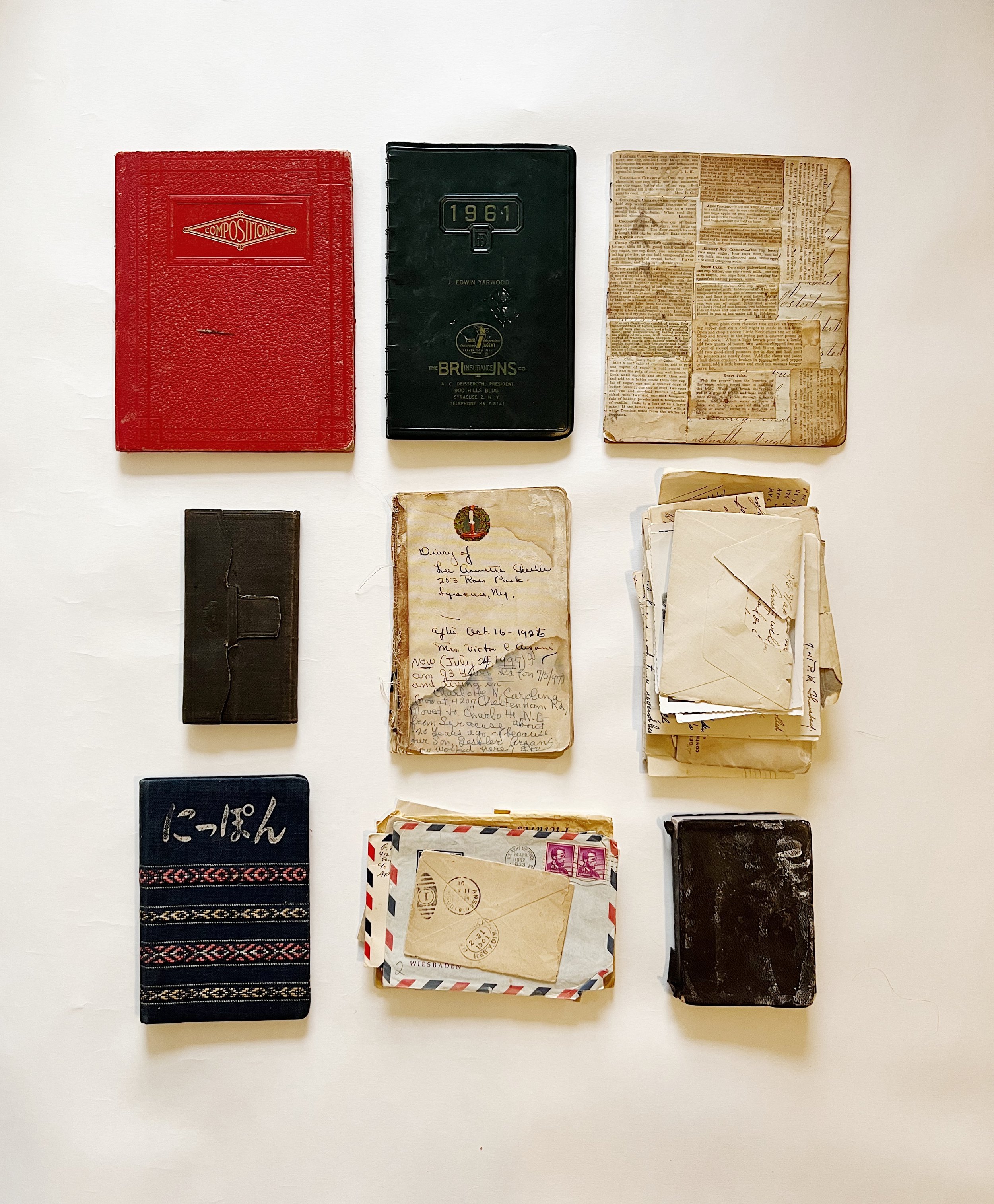

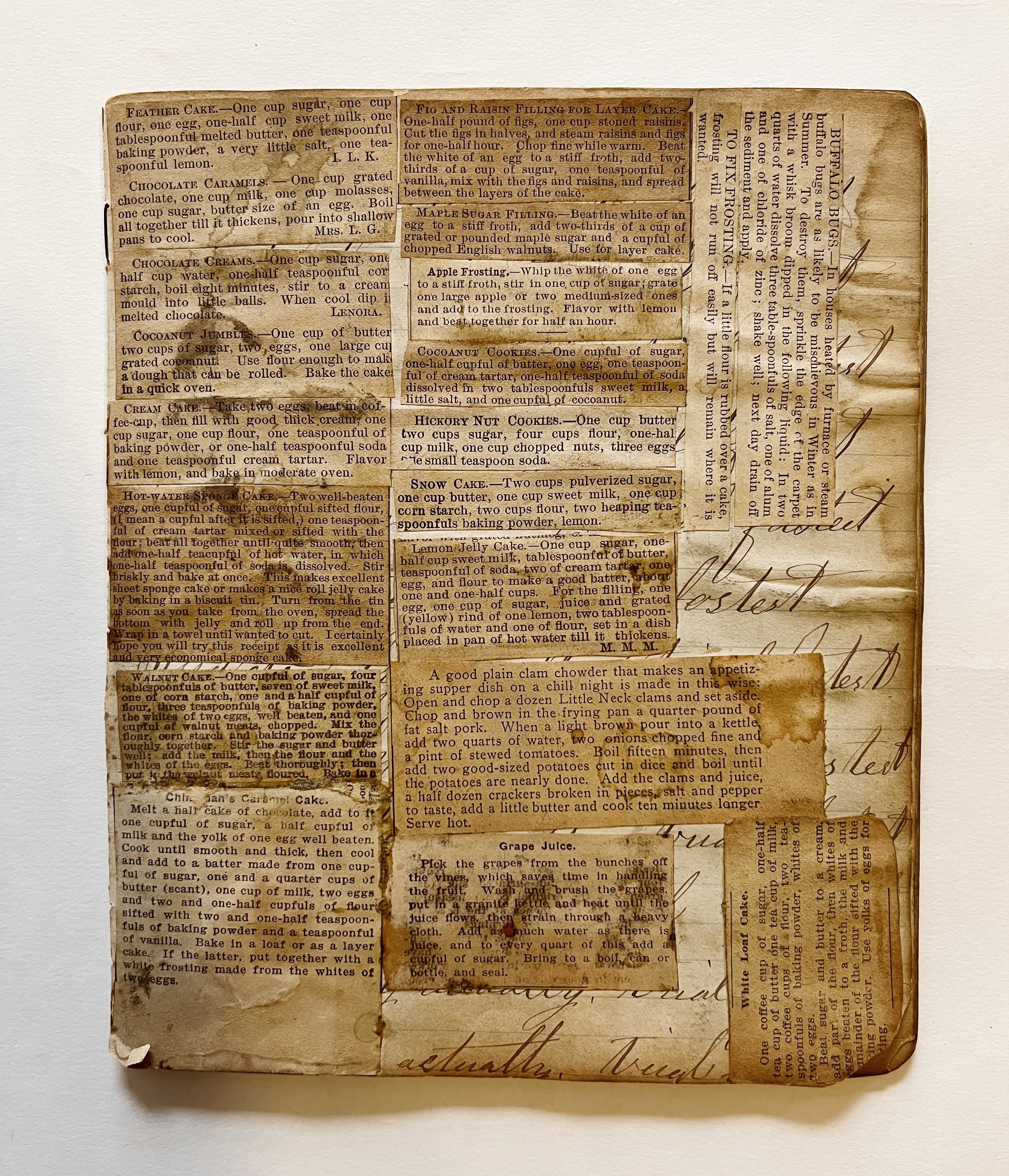

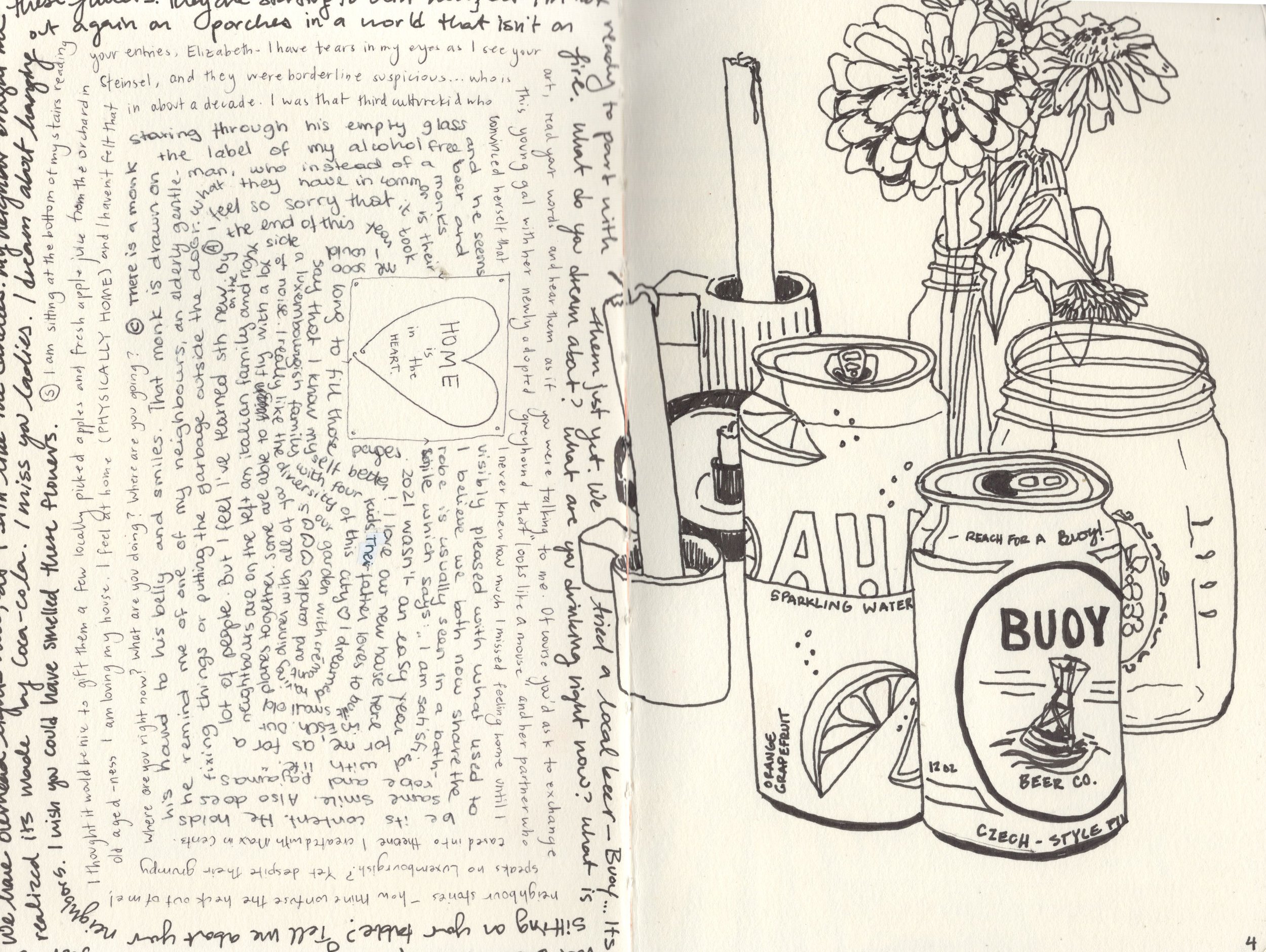

As a collector of sorts, I began to evaluate what I already had on hand. This included my ongoing, six year old list of potential titles— a commonplace of other people’s words culled from books, movies, conversations, and lyrics. It was Jay Ponteri, author of Someone Told Me and Wedlocked: A Memoir who identified this list as a possible poem.

Part of my potential titles list/poem

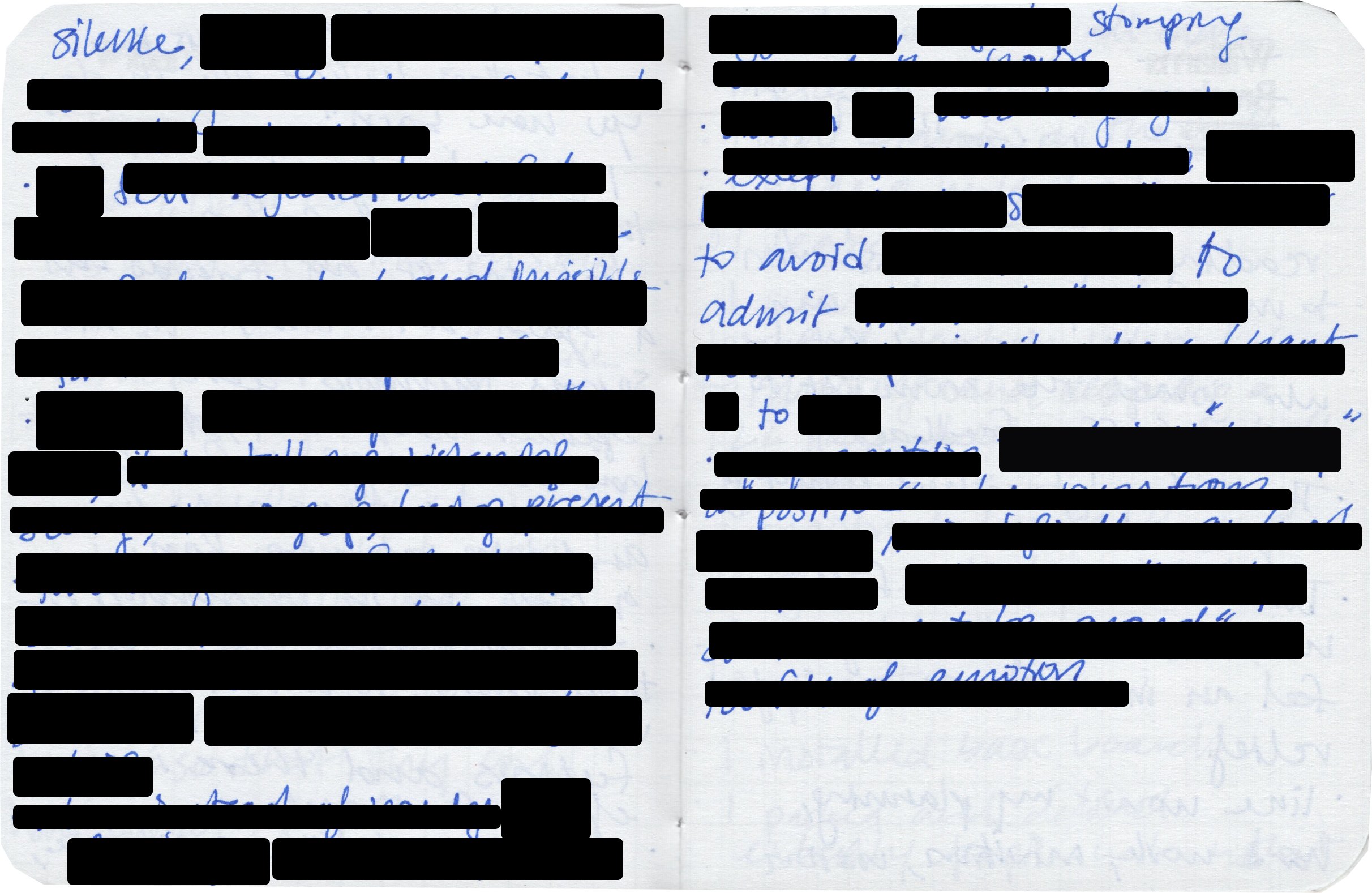

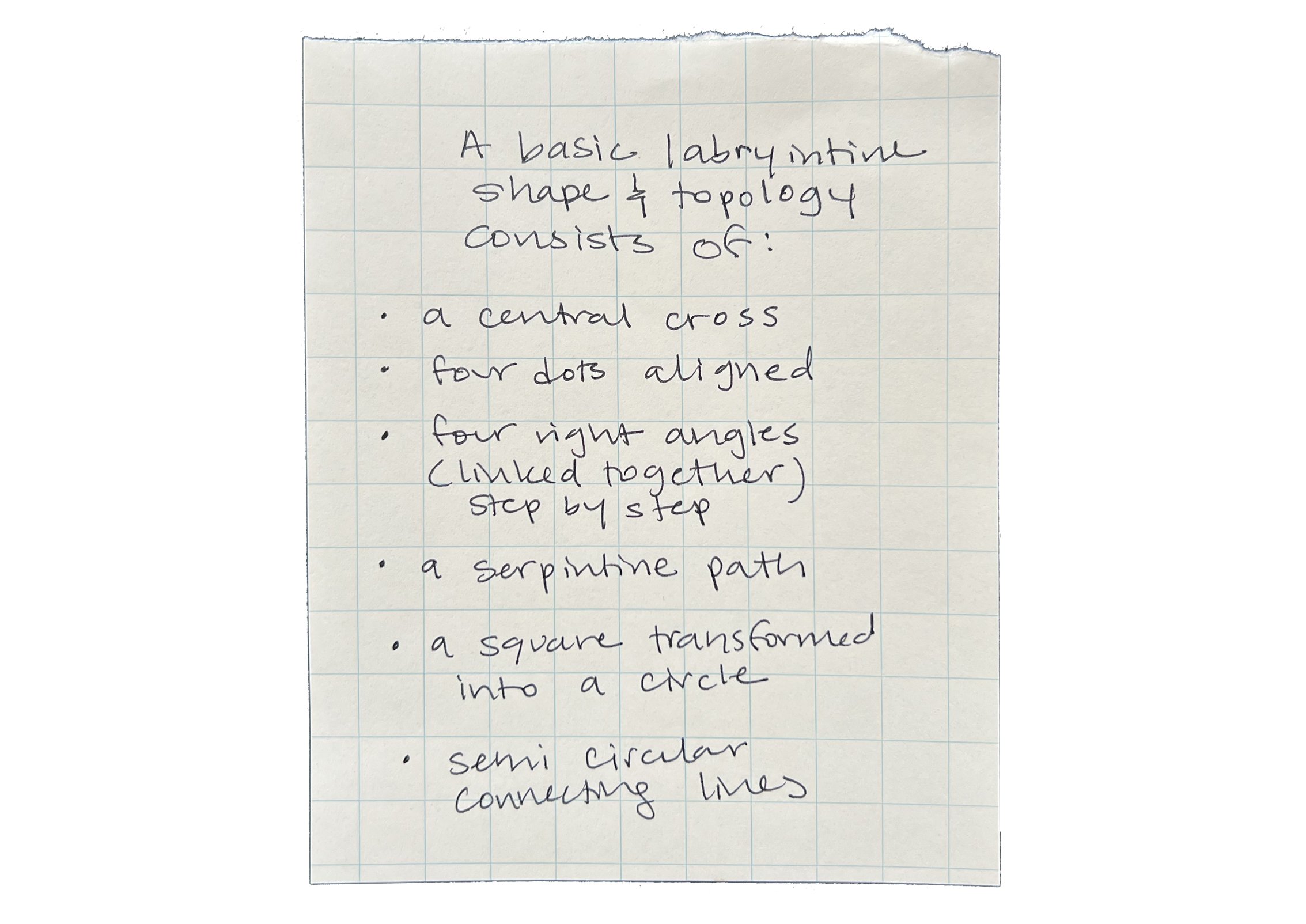

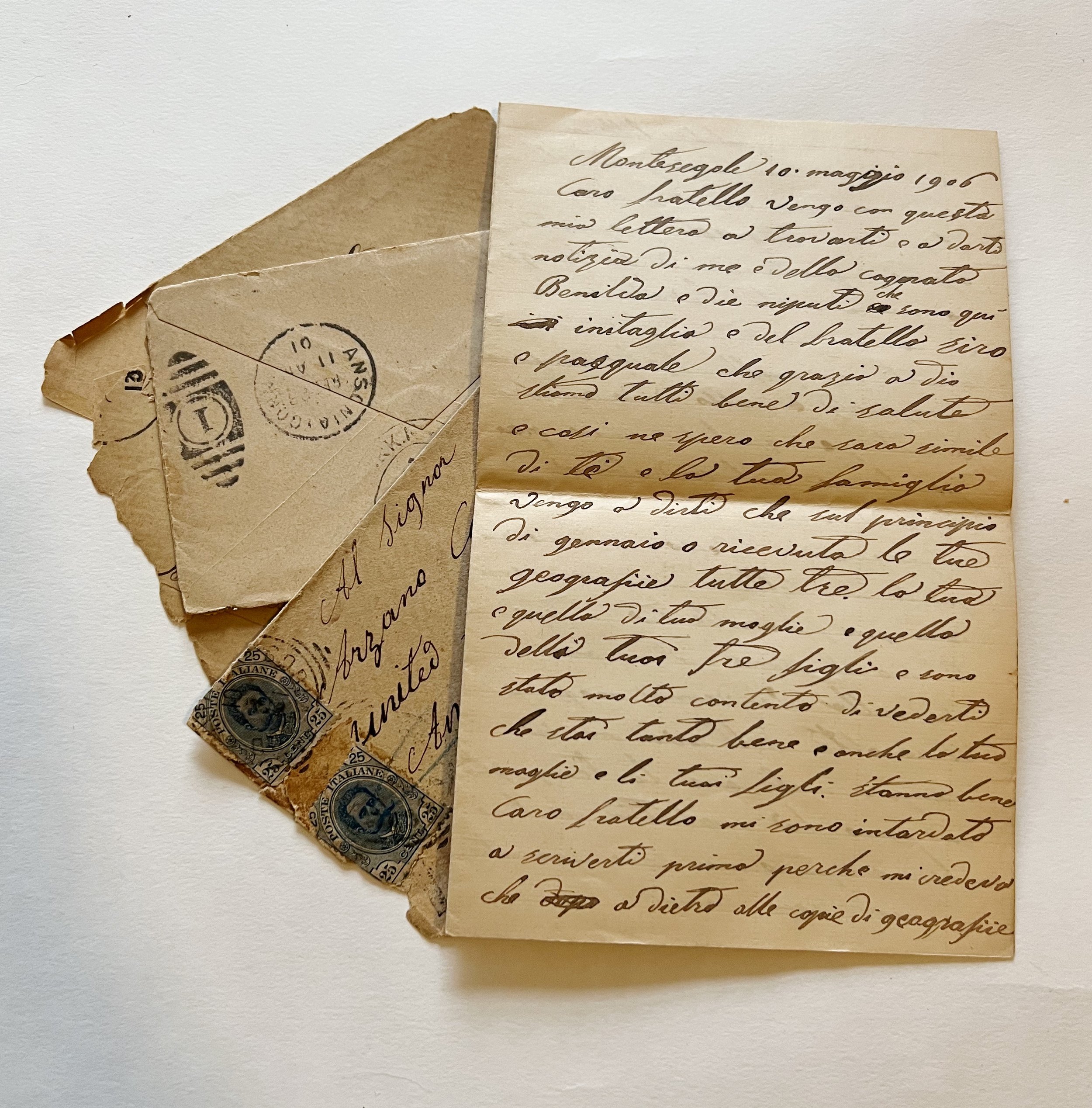

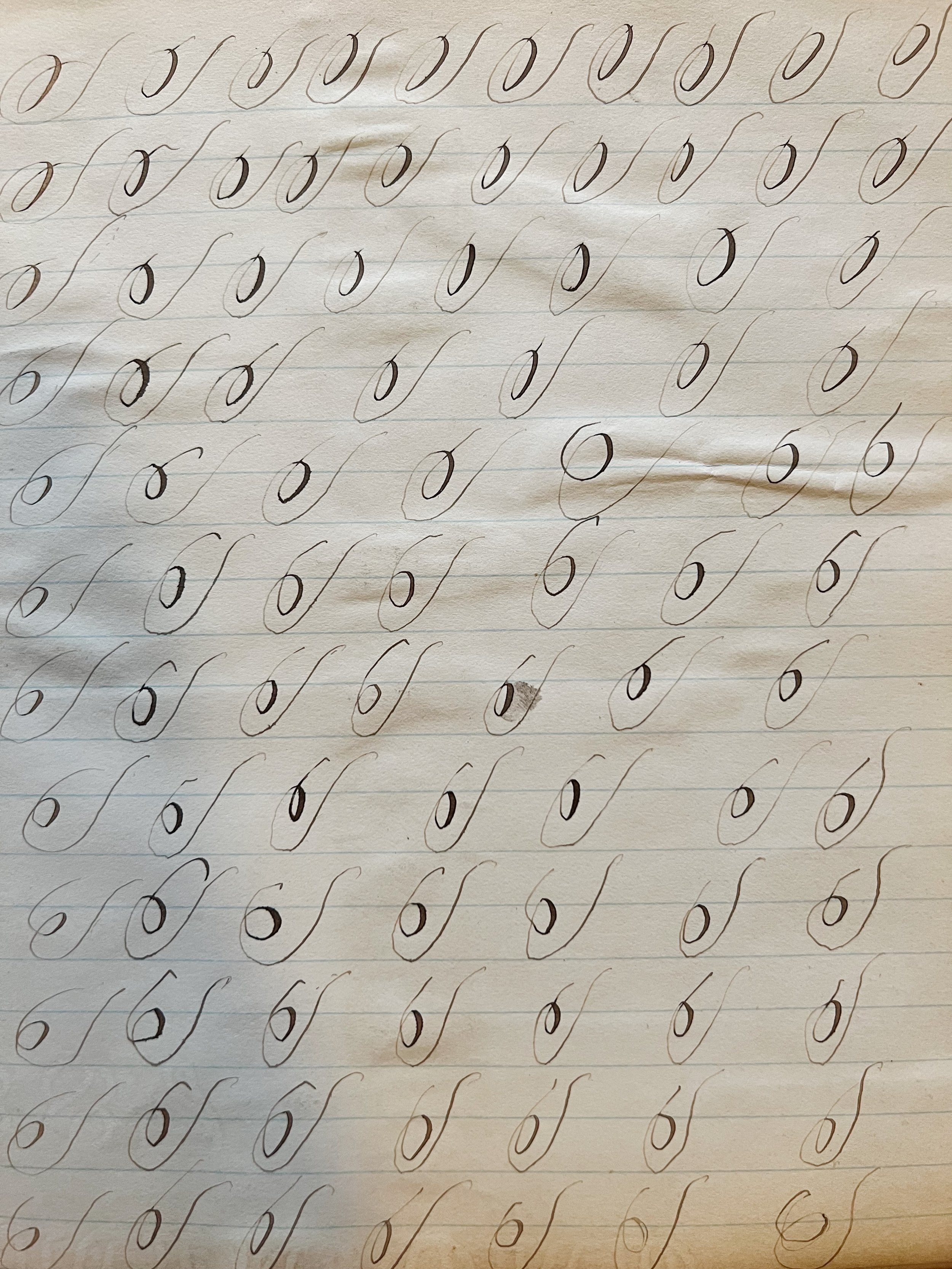

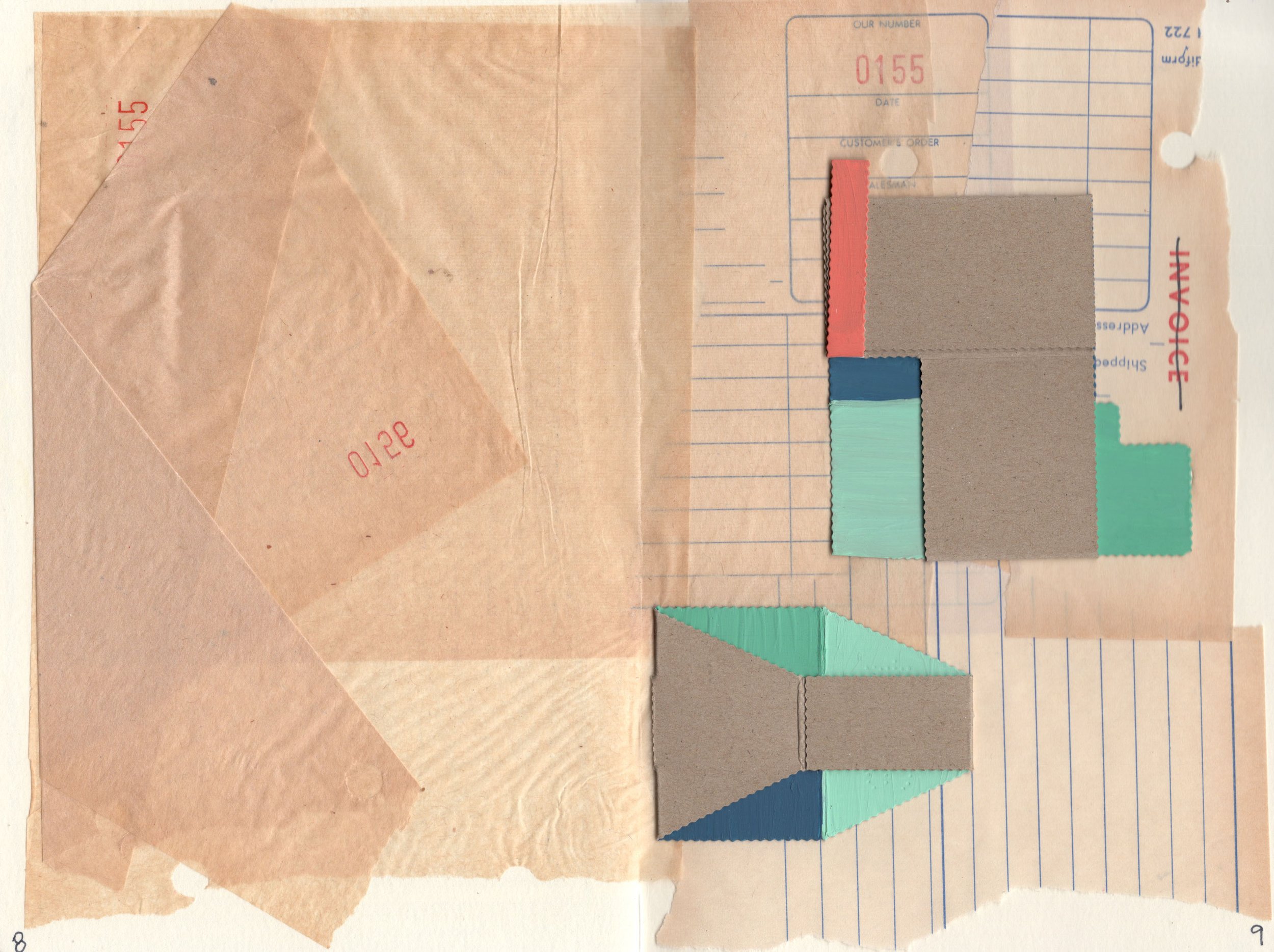

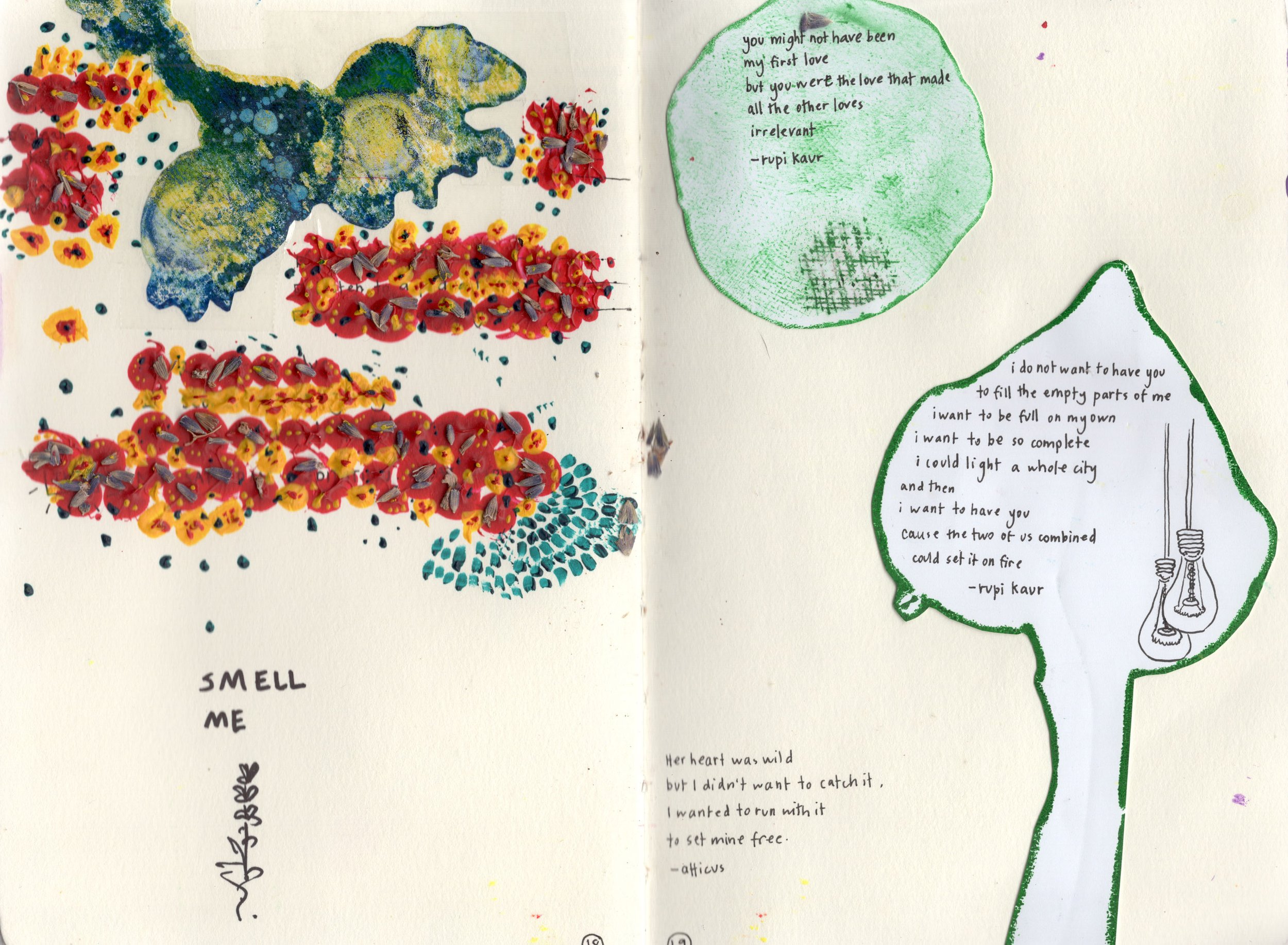

Cento poems are written collages, rearranging words as patchwork. It is important in cento poetry to cite your sources. Yet, my list had many holes. I tried to the best of my ability to go back in time and find the origin of all the words I borrowed.

My attempts recovered some surprising slippages. I found that the phrase the full and the fleeing originated from page 75 of Kate Zambreno’s book, Drifts:

Amina writes me, about the novel she is attempting to write, the desire to write both the full and the fleeting sensations. How to capture that? The problem with dailiness—how to write the day when it escapes us.

I had recorded in my list: the full and the fleeing. Yet, the original text was actually: the full and the fleeting.

And so, this became the title for my solo exhibition at Nightingale Gallery. A slippage in language was the small big discovery that sparked a sudden influx of ideas.

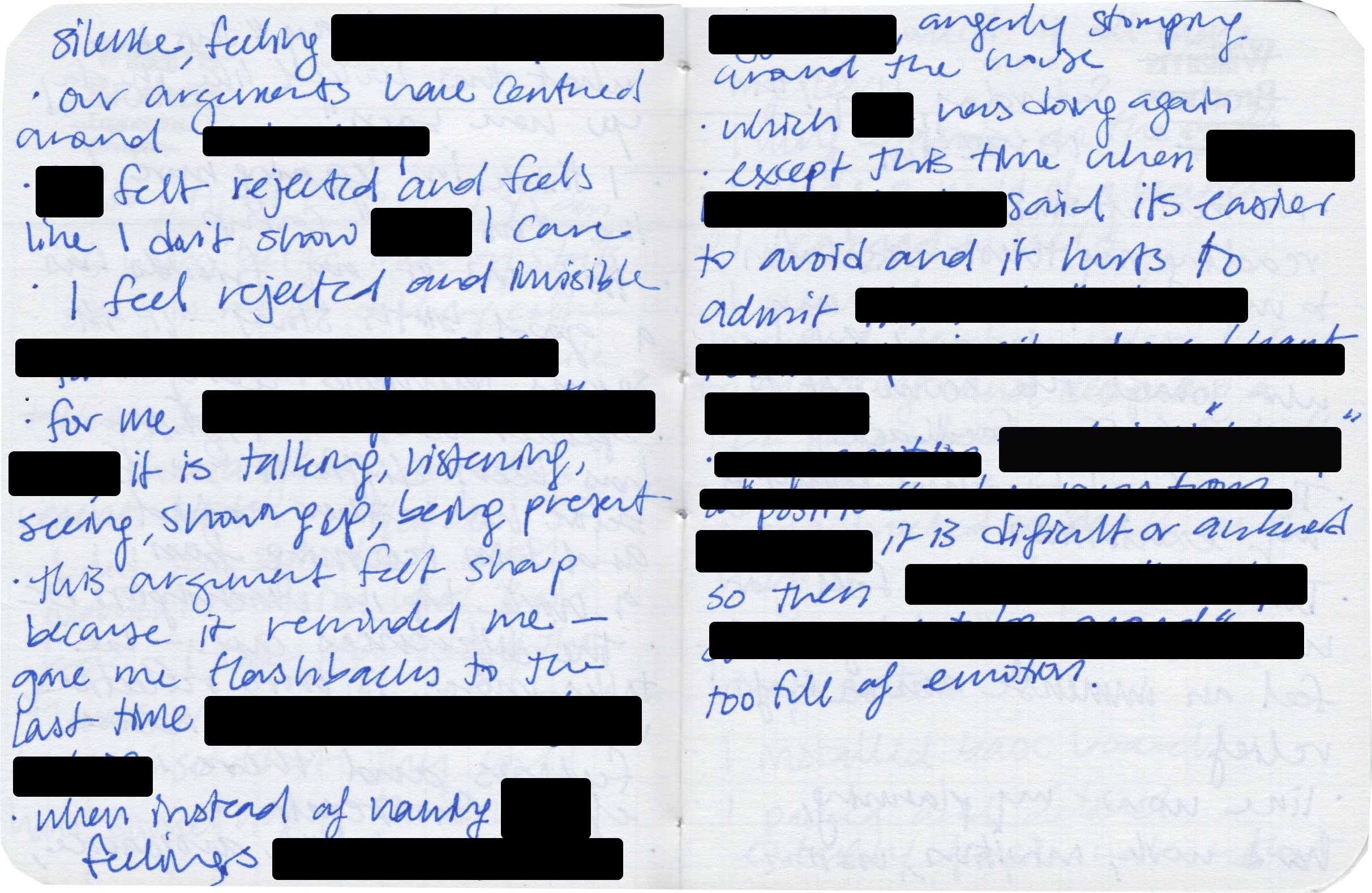

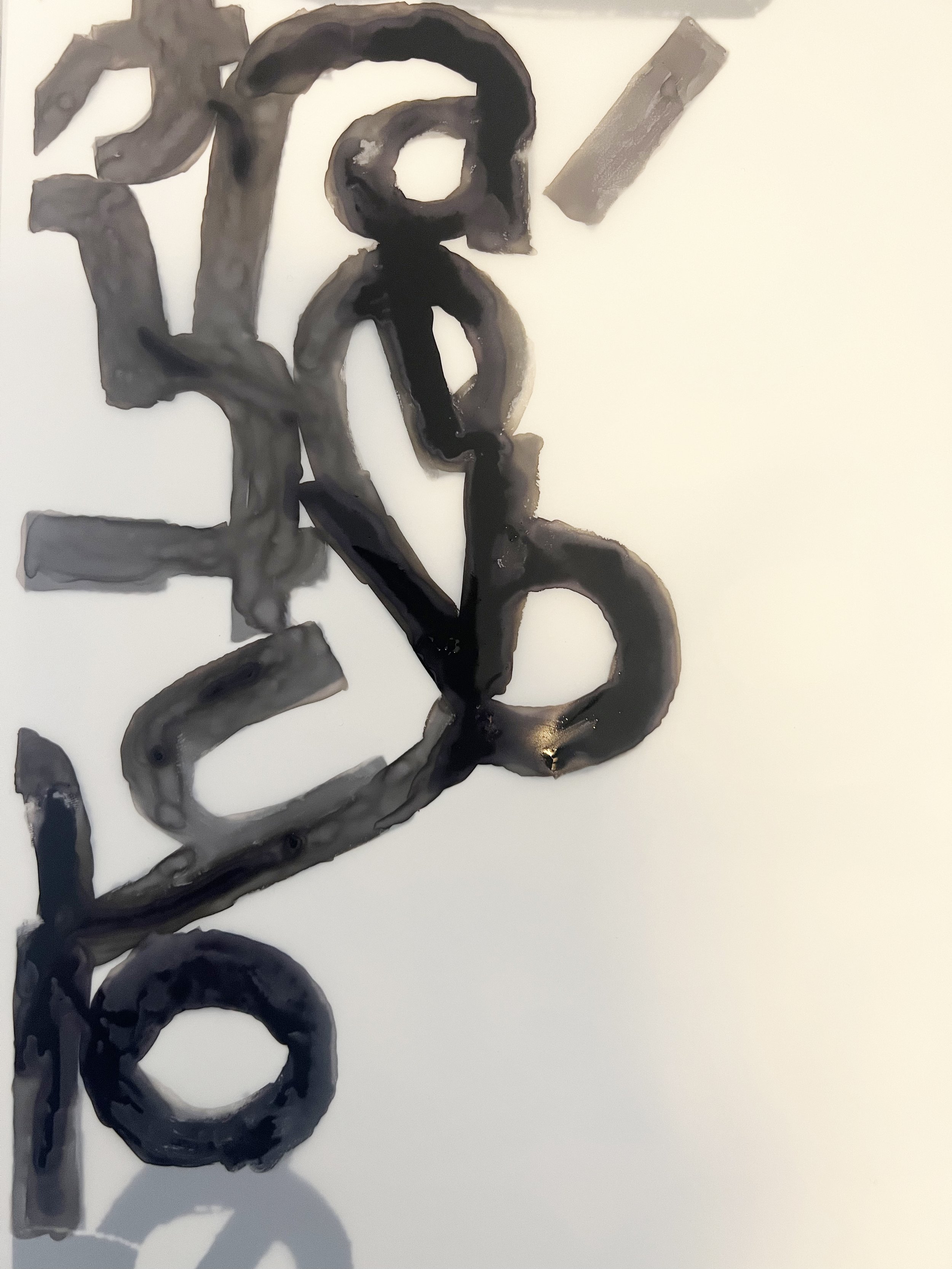

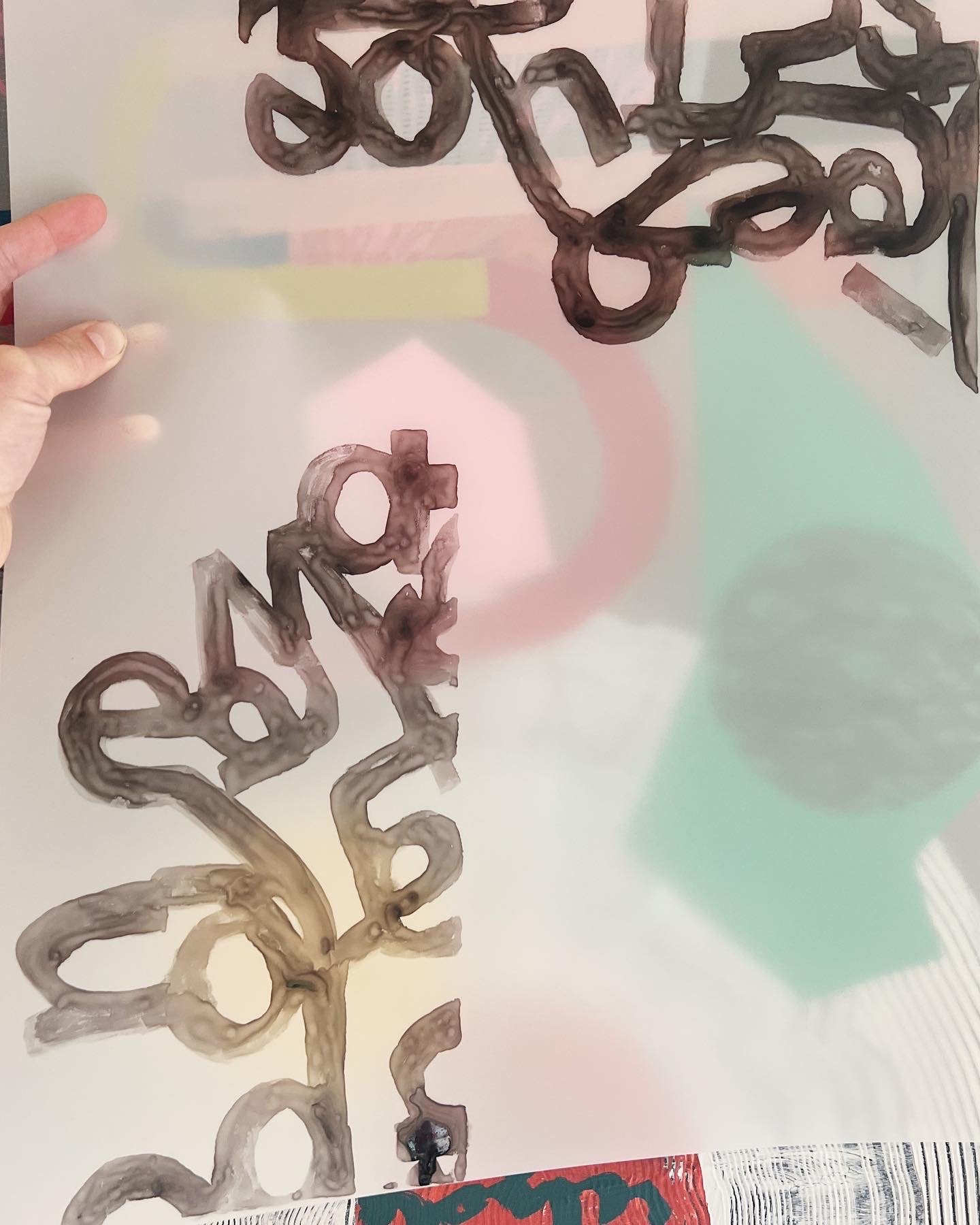

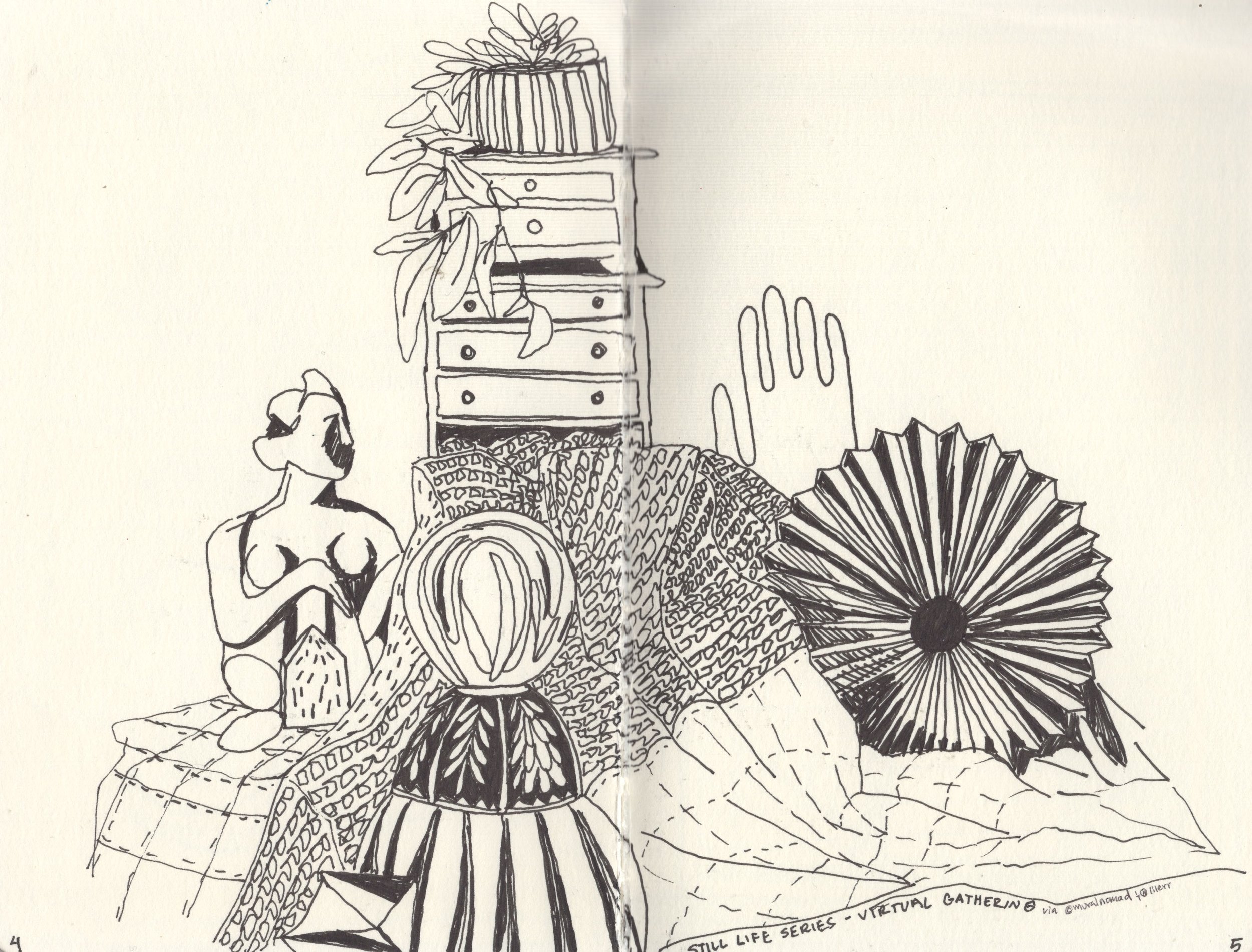

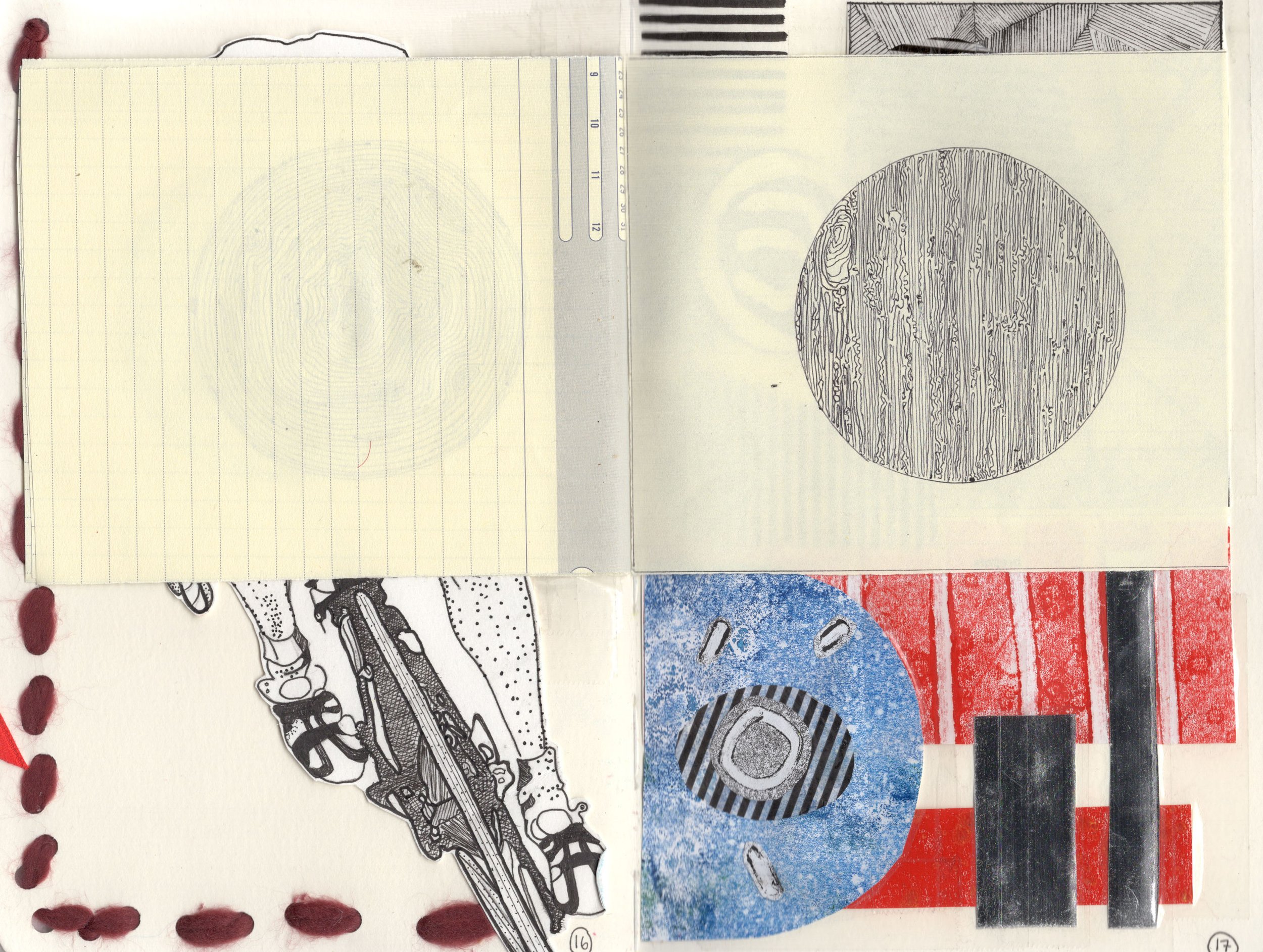

Throughout the exhibition, lines from the cento poems repeated in iterations and echos across works on paper and written in the round wrapping ceramic vessels.

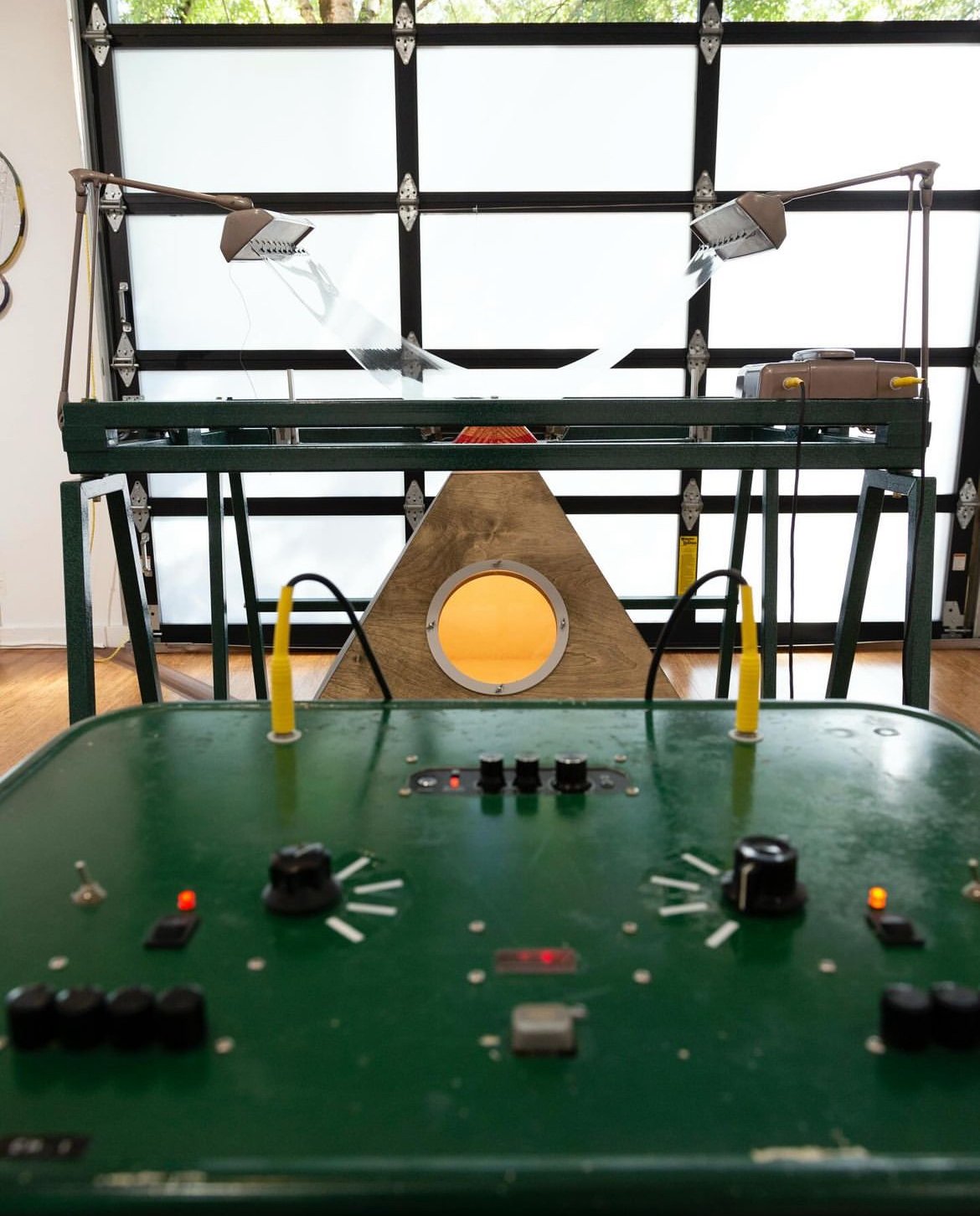

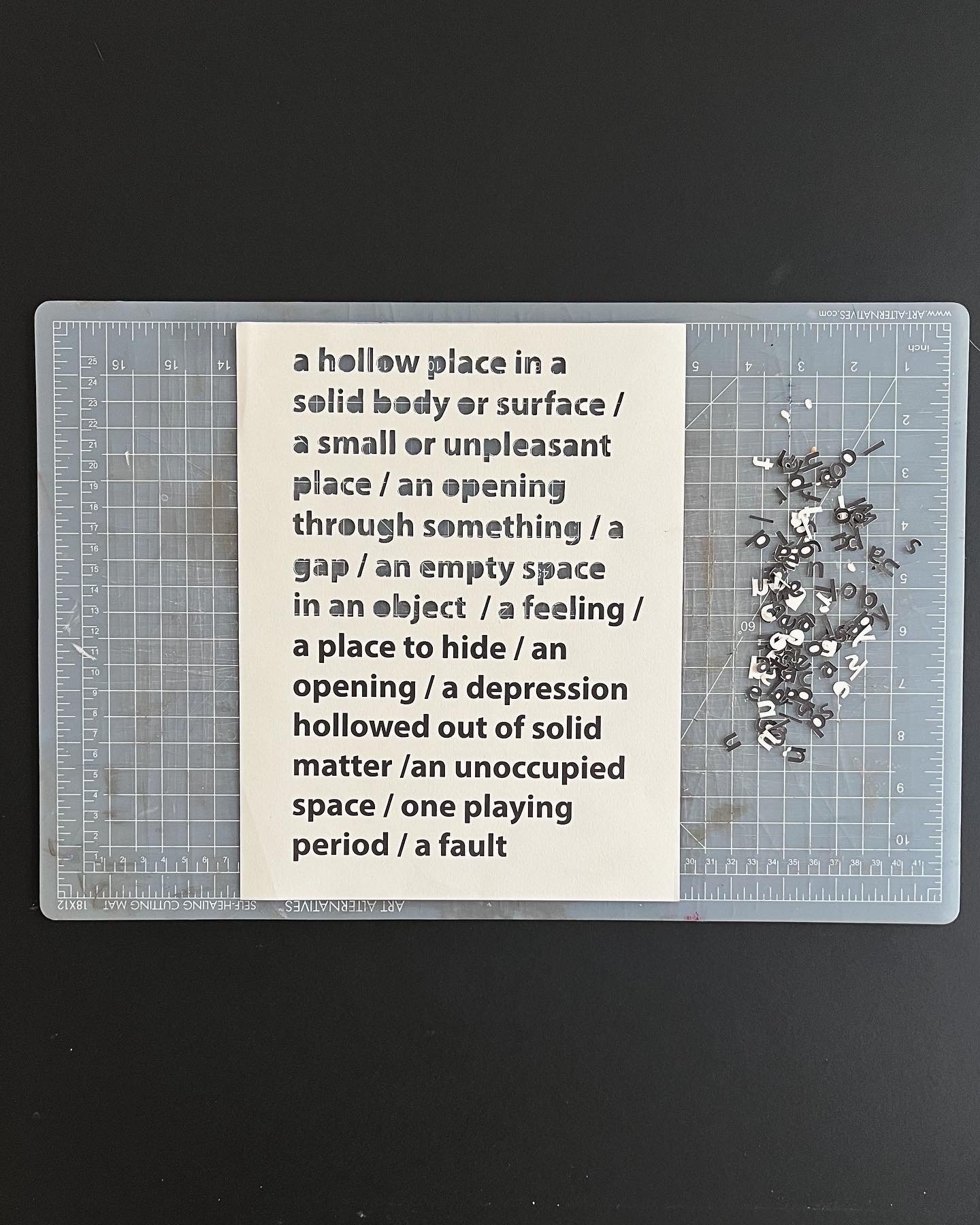

In the works on paper cut out words became holes to peer into, while the ceramic sculptures filled gaps and crevices with collections of detritus and trash from my studio. They became visual and textural notes on the words I consume, throw out, and reject.

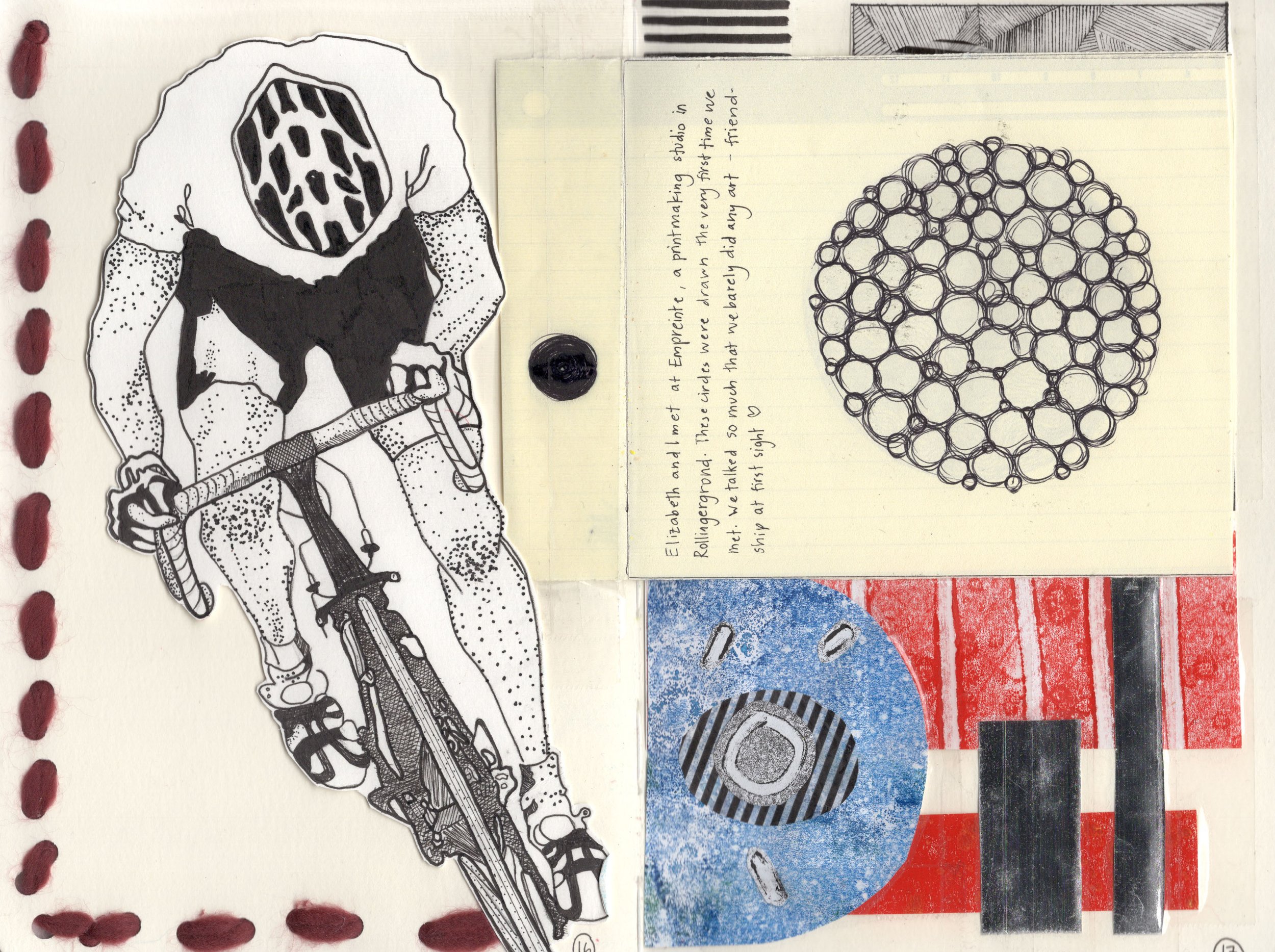

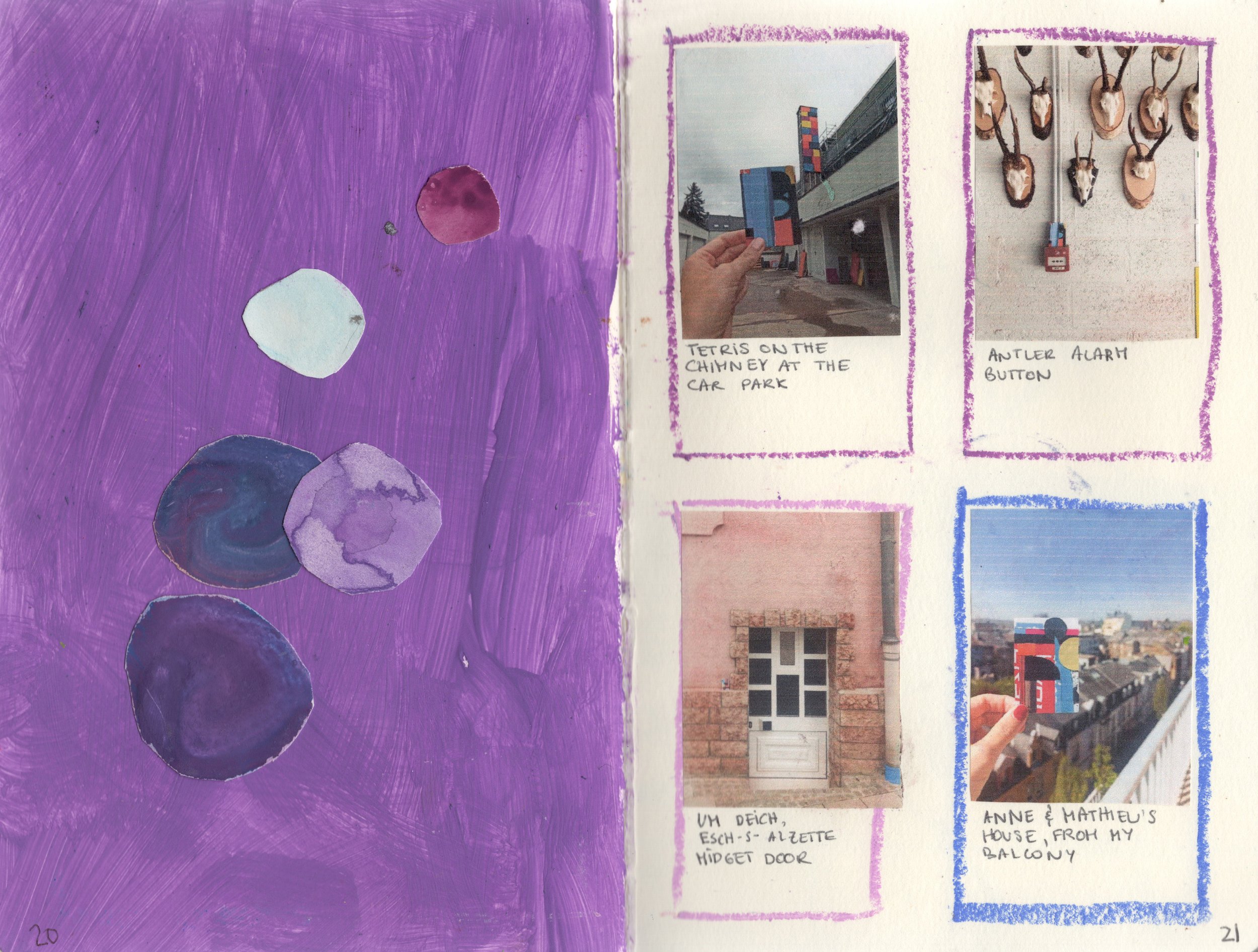

Included in this show was an ongoing project, Sentences I keep near consisting of collections of small works arranged in large configurations that respond differently to each environment, consistently changing.

The component of this project shown at Nightingale Gallery highlighted beginnings and endings to love letters to and from my family members. A hi answered by always yours.

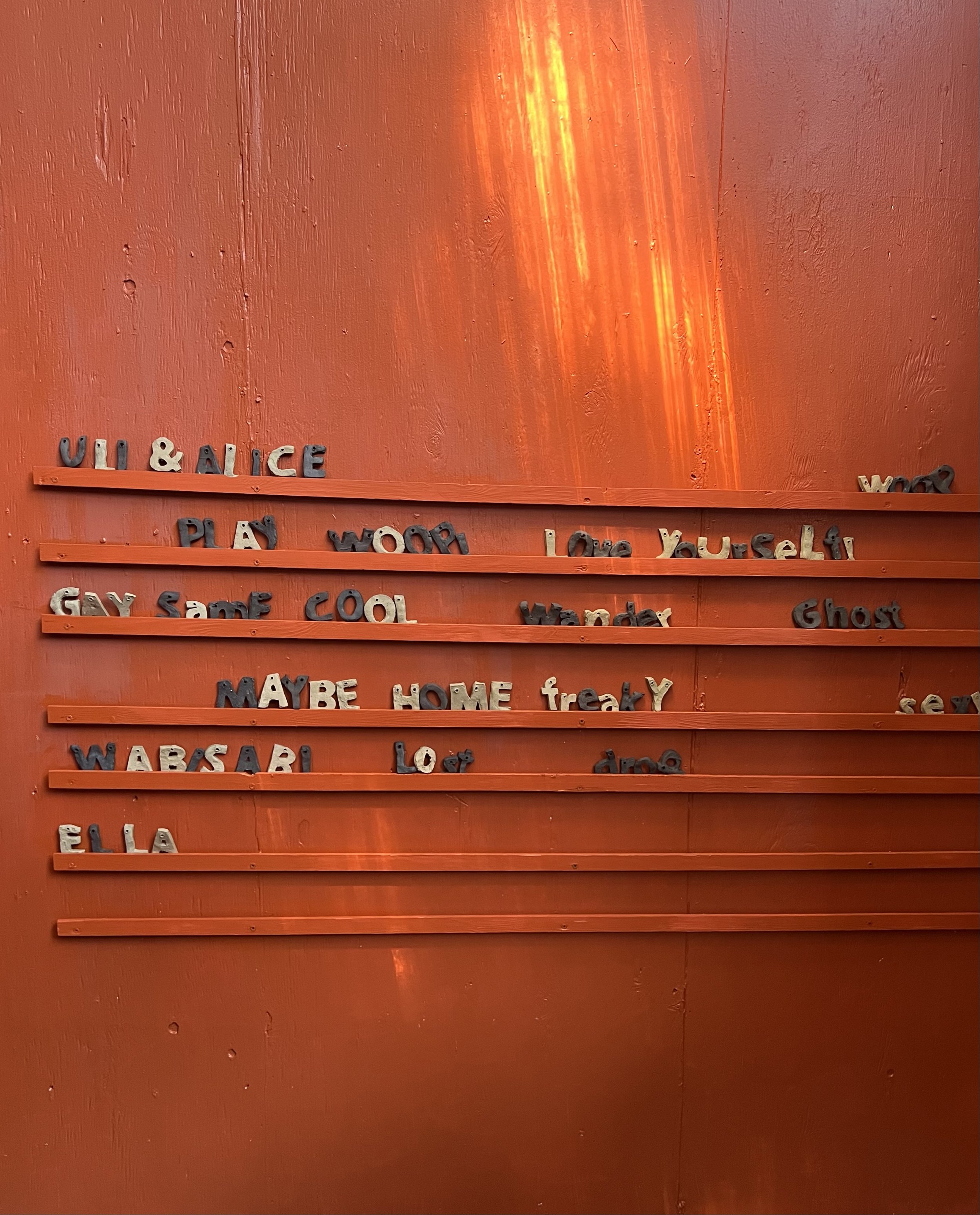

Sharing the other side of the wall, was the installation, writing room presenting the question, what are the words you live with and keep near as an invitation to viewers to respond with their own words on shelves lining the wall.

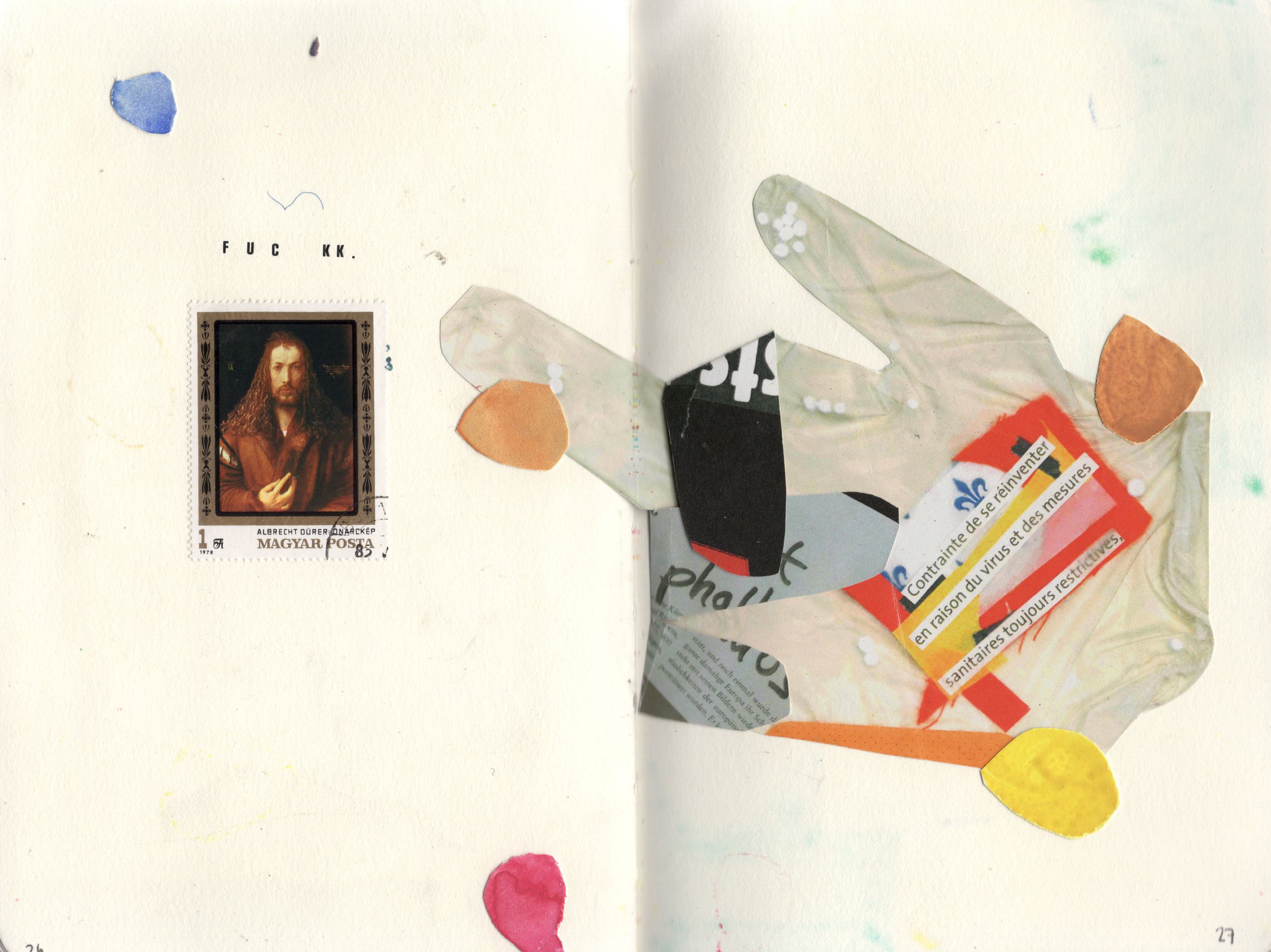

This blue room was the second iteration of a collaborative project that initiated back in 2023 in a backyard shed at 1122 Gallery with ahuva zaslavsky.

Holding approximately 2,000 ceramic letters organized in 26 custom boxes, the writing room was a small room within the bigger gallery, showcasing that an entire installation existed because of small big things: collaboration and conversation.

Some responses by willing participants ranged from: Jesus Loves You AF to trans rights.

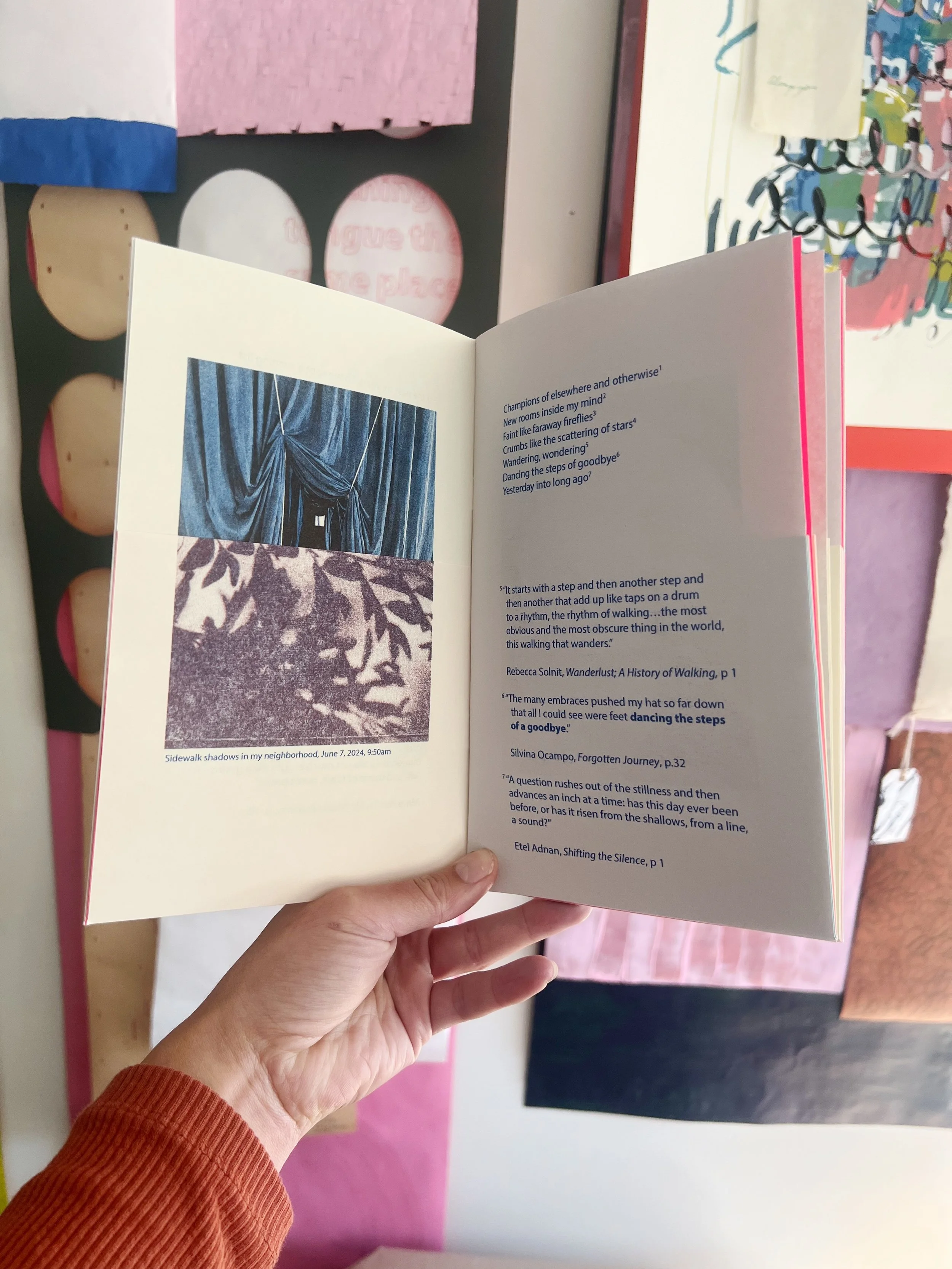

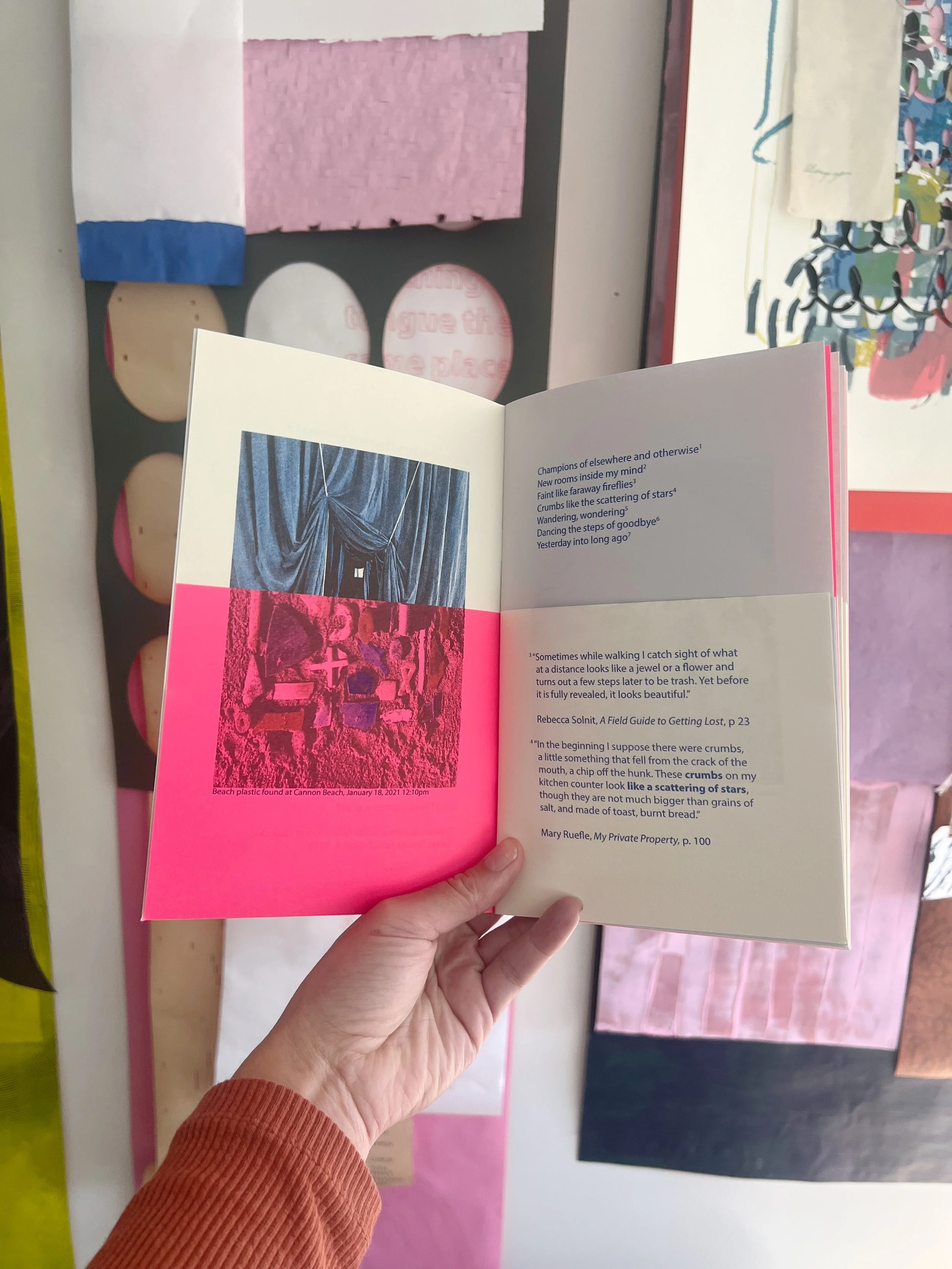

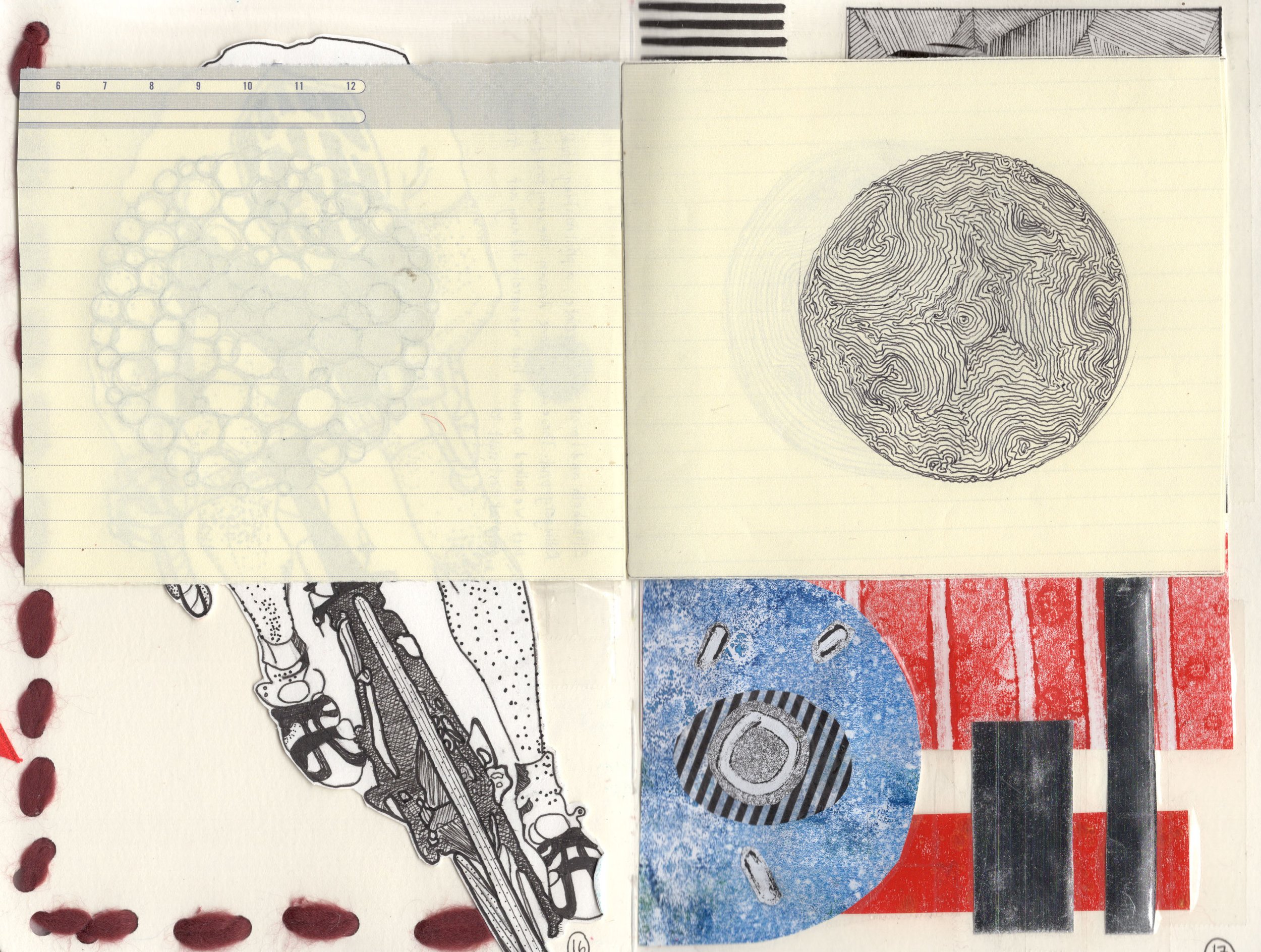

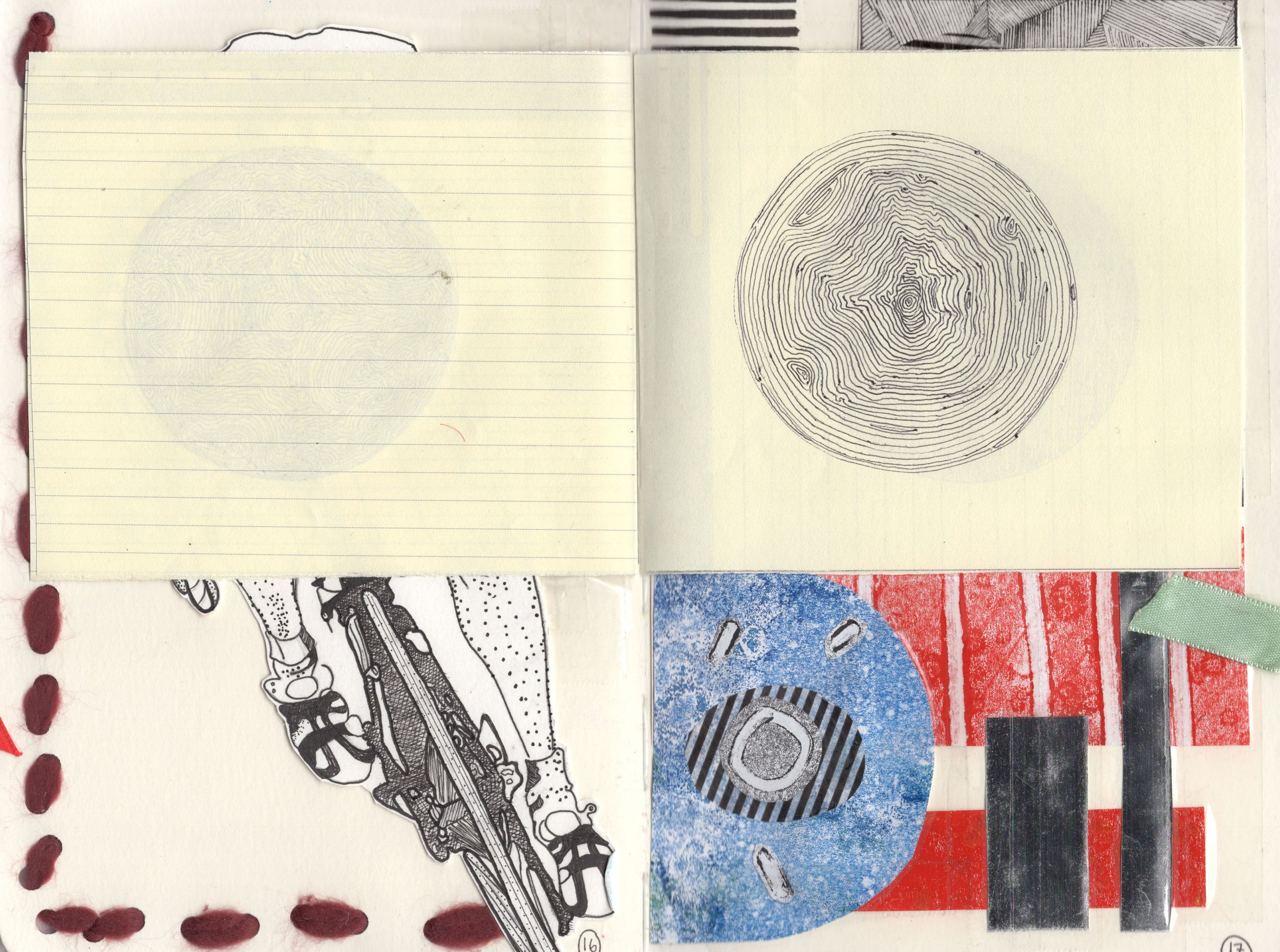

Also presented in this room, was the limited edition artist book, On the tip of my tongue printed by Christina Martin at nůn studios.

This book felt important to be included in the exhibition as it is a compilation of all the cento poems, cited sources and research that appear as corresponding images, changing with each turn of the page.

This exhibition taught me that the answer to the question of how many artworks can fill a large gallery and also still fit within one vehicle is: 63 pieces.

To learn more about this project you can watch the recorded artist talk below.

Thank you to everyone who visited and supported the making of The Full and The Fleeting, including EOU faculty, Susan Murrell for hosting me around La Grande, Nightingale Gallery Director, Cory Peeke, Student Gallery Director, Jack Hess, and the many more gallery assistants who helped with this show.

Exhibition documentation by Yasser Marte.