How many ‘nevers’ have you told yourself? These are the ‘I can’t’ statements or the ‘I will never’ thoughts that permeate beliefs and inform behaviors. The stems of self doubt. A self imposed never stops you before you have the chance to start.

Rick Ruben, record producer and founder of Def Jam Records wrote about this in his book, The Creative Act: A Way of Being. He lists never statements under the heading: Thoughts and habits not conducive to the work.

The work being: creativity.

Pages 138-139 from The Creative Act: A Way of Being by Rick Ruben

Ironically, before reading Ruben’s new(ish) book, I fought hard against my own self imposed rule: never go to a book club if you haven’t read the book. Hesitantly, I picked apart the word, ‘never,’ taking the letter ‘n’ away, but keeping ‘ever’ —at any time. At all times; always. In any way.

I showed up with my barely opened copy. Sitting in a circle under a shaded tree in the park, I found myself next to a very indexed version of underlined and dog-eared pages and by the just-finished book, across from the admittedly half-way there book. Regardless of our re-read or not-yet-read pages, we found that we had all arrived at the same vulnerable feeling: we are never doing enough.

Never statements are lonely and rarely admitted out loud. Why is this? Why is it is so much harder to say I am enough and believe it?

Ruben identifies habits—our movements, speech, thought, and perception as pathways carved into our brains, functioning autonomously and automatically. It is painful, awkward, and uncomfortable to unlearn or to create a new behavior or habit, or to even recognize when one is no longer serving you.

For my latest two person exhibition, Recieving Space with Owen Premore at Souvenir gallery this past September, I showed a new series of works on paper that initiated with the phrase: to pick up words from the ground never opened.

This phrase recounts the time I found fragmented letter forms lying on the ground in a field while out for a run.

Collection of letter forms stuffed in my pockets

The happenstance of stopping to notice waterlogged cardboard pieces that had dislodged themselves from an obscure site-specific cement sculpture a few yards away gave me the immediate feeling of being right where I should be. It was random that I happened to be running. Yet, being in a small town for a month at an artist residency without a car led me to attempt to explore a new place on foot.

Just as Ruben described the importance of creating sustainable rituals to support creativity, he also notes that inspiration is hidden in the most ordinary moments and the possibilities that emerge when you are able to stay open and pay close attention.

Inspiration - #29 out of 78 areas of thought from The Creative Act: A Way of Being by Rick Ruben

Curious, I collected as many torn cardboard pieces as my pockets could hold, imagining all the words they might have said. It may sound silly, but truthfully I’ve been thinking about these little scraps of paper for over a year. Previously they have served as my starting point for plaster molds and ceramic sculptures, but most recently, I’ve been using them as material for writing, weaving, and printmaking.

And so, I typed to pick up words from the ground never opened several times across many pages before slicing the printed text into one inch strips and weaving them back together. Each letter form undulated in an over and under pattern to arrive at one interlocking structure. Opened intertwined with never.

Scanning my woven words allowed me to digitally cut and crop, zoom in and out, further reducing each word to isolated islands or fragmented fields. They became a new field of flat color whenever the digital scan was translated back into a physical material with ink squeegeed through the stenciled mesh of a screen and printed on paper.

The more each new found shape obscured it’s root in language as I screen printed layer upon layer, I found myself missing the in-between moments. Moments of almost reading or noticing the seemingly familiar. The space where words feel slippery or hard to distinguish after letters have been crammed in my pockets or displaced in a field near the woods.

I wanted to get back to the moment where something about a fragmented form of a lost letter compelled me to stop and look closer.

Collecting found fragments is simultaneously about what remains just as much as it is about what was is lost.

Fragments emphasize the negative space, the we-know-not-whats, the silences—the holes. It might be the beginning of a love letter; words held dearly until they became tattered from wear and tear. Or the opposite, the words we let go—unspoken, ignored, swallowed whole, never opened.

This same sentiment is applied to my wall sculptures, tin collages or assemblages presented in this show. This year marks ten years of tinkering (on and off) with Bill Herberholtz’s gifted collection of vintage and salvaged tin.

Just like how I found the fragmented letter forms in the field, Bill’s collection was given to me in bits and pieces.

Sometimes it took years for me to identify the origin of a material after spotting it in it’s original function out in the world.

These pieces are your old containers, retro dollhouses, trunks, signage, toys and trains. Seeing only parts of the whole, made me pay close attention to the specificity of color and the mark making made by rust and usage. They were my clues to the life of these objects.

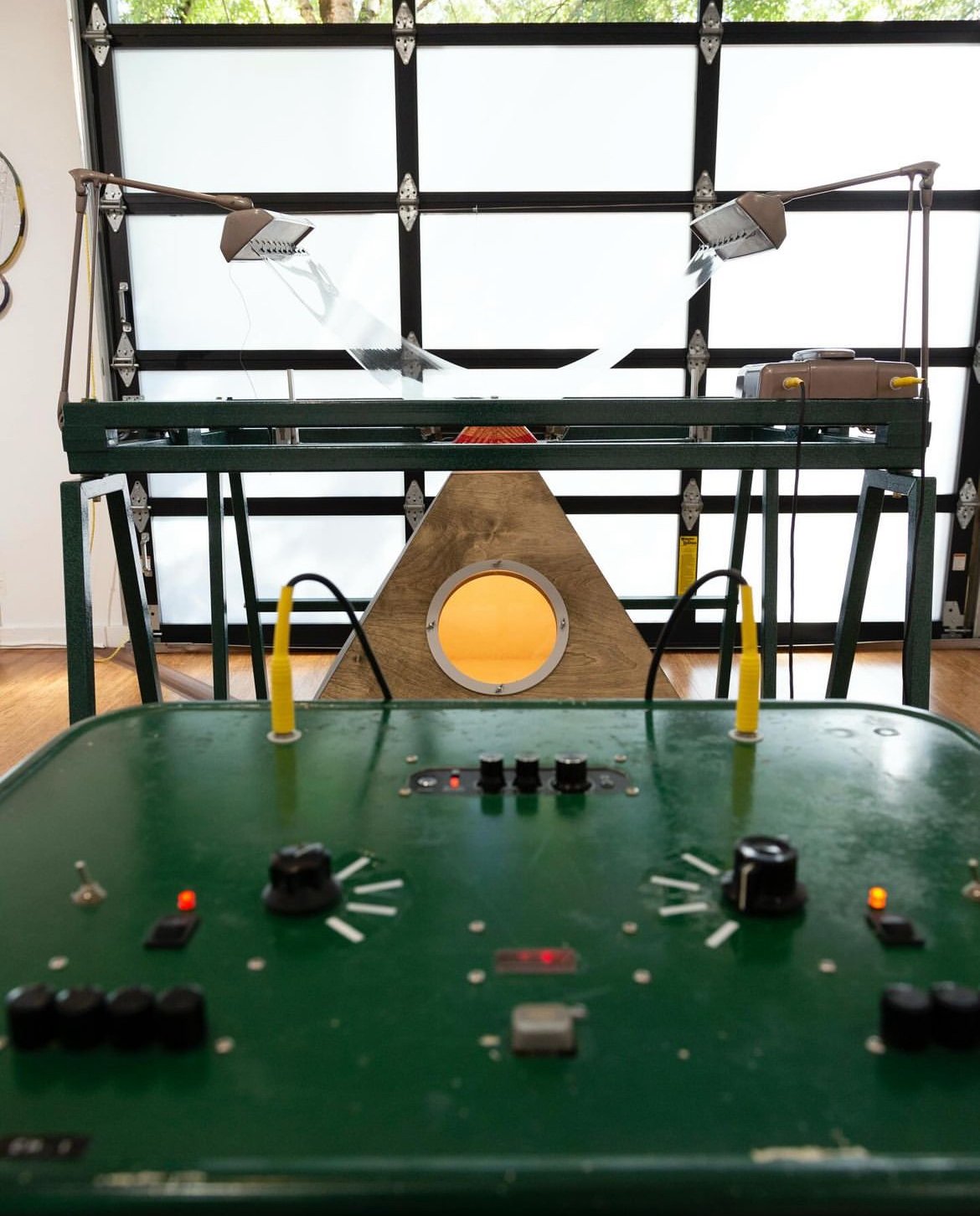

Prior to our two-person exhibition, Owen and I had never met. We worked asynchronously from our respective studio corners, introducing ourselves over phone calls, wishing each other luck as our deadline approached. It was Owen’s description of his 'Heavy Time’ series as absurd, noisy, unexpected, a series of humorous contraptions that piqued my interest the most.

Hearing about his process of seeking out strange combinations of material and sound, inspired me to revisit my own strange collections of material at hand.

From my notes taken during our conversations, I circled the word absurdity and drew arrows linking the material of found objects to the experience of way too much information all at once. This experience was a reference to the heaviness of the times—COVID, stress, and cyclical media as being hard to process individually and all together absurd.

When I asked what kind of sounds his sculptures made, Owen shared there was one with multiple metronomes that recorded on the “tick” and played back on the “tock” resulting in what he described as an “out-of-sink static or glitchy sound”.

While I didn’t quite follow all the mechanics or engineering involved, I gleaned that the sounds emitted from his crystal radios would be even more elusive since they pick up different stations or noise depending on their location and proximity to other variables.

At one point during the opening reception, I saw people tuned into each radio or sculpture either by foot pedal, knob, or touching a coiled antenna.

It was a conglomeration of low hums, beeps, a click click, a high noted sharp squeal, a marble rolling, a ding, a buzz, a bang, followed by steady static and a short burst of a fuzzy radio station with muffled voices. Each arrangement of sounds would be different every time I visited the gallery.

Installation view of Receiving Space, September 2024 at Souvenir

Shown together in Receiving Space, our work transmitted varying levels of visual and auditory noise: the miscommunications, beyond-known-sciences, the paranormal, and the unknown. Here, even silence felt loud.

Huge thank you to Doug Burns, director of Souvenir for supporting this exhibition.