Stepping over the knotted red rope, with coffee and donuts in hand, we took our seats, circled together in the space of the gallery called the arena.

Coffee Talk in The Arena

Here, artists and longtime best friends Nan Curtis and Mk Guth gathered to lead a conversational artist talk, a ‘Coffee Talk,’ discussing Cairnatopia, Nan’s recent solo exhibition in a raw, unfinished, unpainted space; presenting artwork installed between walls of visible pink insulation.

This show, hosted by Sator Projects, is one in a series of migrating exhibitions directed by Jess Nickel, whose mission is to utilize overlooked spaces as seeds for bringing art to the community.

I have worked closely with Nan (and MK too). Nan was my mentor my last semester of grad school and in many ways continues to be. Leading up to this show, I worked as her artist assistant, spending summer days sweating in the studio and late afternoons swimming in her backyard pool.

Despite our extended time together, it was from inside the red roped arena where I was hearing of her collection commission series for the first time. I am not sure whether it was mentioned before or after the unanswered question, “can you make art out of anything?” But it was most likely this rhetorical remark that shifted our group conversation.

Studio notes between Nan & Jessie, 2022

Hearing Nan recall being commissioned to work with other people’s collections, with random and very specific things like a stack of old exhibition cards, or a family collection of inherited lace from Europe, flooded me with a myriad of would you ever possibilities. Ideas which I am still churning over in my head.

At that moment, I eagerly and instinctually raised my hand, injecting myself into the conversation to ask, “are you currently accepting submissions?”

“Yes.”

But before each project begins, a commission form and questionnaire has to be completed. It turns out this series initiated as part of The Rekindling, a 2011 exhibition at The Nine Gallery, an administratively and financially independent, artist-run space situated within Blue Sky Gallery, Oregon Center for Photography. It was here, eleven years ago that Nan’s first collection commission began.

In the essay, Coming Clean, Portland based director and curator Stephanie Snyder reflected on her own relationship with collecting, stating that in her childhood experience, collecting was a way of organizing the things around her—a way to cope.

“We tend to build collections when we’re young, and as we age, we experience the weight and burden of ownership. We purchase, we haul, we sort and store, and eventually we inherit. Sometimes we hoard. It all becomes too much at a certain point—a landscape of physical and emotional baggage. And yet we peruse the objects of others’ lives, amassed in thrift stores and spread on tables at estate sales, and we re-locate ourselves and our memories there.”

Stephanie Snyder, Coming Clean, The Rekindling , pg 13

For Nan, place, memory, and emotion are marked by piles. Interactive, stoic, playful and unpredictably bouncy, these piles stand, droop, tilt, and lean–they haunt; they greet us when we look up, nestled in the rafters above our heads or ask us to stop and look down when placed discretely at your feet. Their presence is a way of navigating the seen and unseen. Cairnatopia, recalls a long history of marking with piles.

“A cairn is a marker, a memorial, a constructed object — a memory arranged for a space and viewer. Historically, a cairn is constructed of piled rocks, ranging in type from as few as three to mark a trail to as large as a hillside. They pre-date history and can be found in every culture across the globe, the simple and universal act of a person stacking, making a pile from the objects around them to make a mark, preserve a memory or send a message.”

Ashley Gifford, founder of Art & About

The rocks in Nan’s current exhibition, both the illuminated glass and the flocked plaster were made from molds of a rock that Nan had taken with her to Yucca Valley Material Lab, a place known for material curiosity.

Opening Night of Cairnatopia, 2022

Heidi Schwegler founder of YVML recently wrote about the objects she encounters in the desert. In the essay, Single Use, Schwegler defines nature as an ‘unintended craftsperson.’

In the desert, the Santa Ana winds reshape neglected material. Trees and cacti become an array of tools: hole-punchers, nails, and push pins, armatures for molding and nets for catching. The desert sun bleaches color, with time peeling it away from its outermost layer. Schwegler refers to all making processes (both environmental and human) as varying ‘levels of pressure and resistance.’

Yet, Schwegler also claims that ‘once something is made we are forever tasked with stalling its natural tendency towards breakdown and disorder. Disconnected from use-value it may still exist in our world (like a ruin) but has been reduced to a mere presentation of the past.’

As part of my new job as an Assistant Studio Manager for Wildcraft Studio School, I am often assisting with a variety of classes that revitalize craft traditions. In a Sashiko Japanese Mending workshop, I learned from Tyler Peterson that the term ‘sashiko’ translates to ‘little stabs’ or ‘little pierce.’

It is both a decorative and functional form of embroidery used as a way to extend the life of each inch of fabric. Mottainai, meaning ‘do not waste,’ is another Japanese term I learned from Tyler, referring to a deep reverence for material and the desire not to squander…a practical need for repair.

After assisting with several weaving classes, whether it was ripping up and repurposing old bed linens and braiding them into a rug or prepping himalayan blackberries for cordage and basket weaving, I’ve become more interested in learning different ways to weave. I can’t help but wonder if this new interest is a natural tendency to stall the inevitable.

In Francesca Capone’s Light Journal, a book about ‘colorful tapestries of text in time,’ she compares the act of writing to the act of weaving. While I am not experienced on a loom, I have been weaving stories in one way or another since I can remember. Collecting is an act of storytelling.

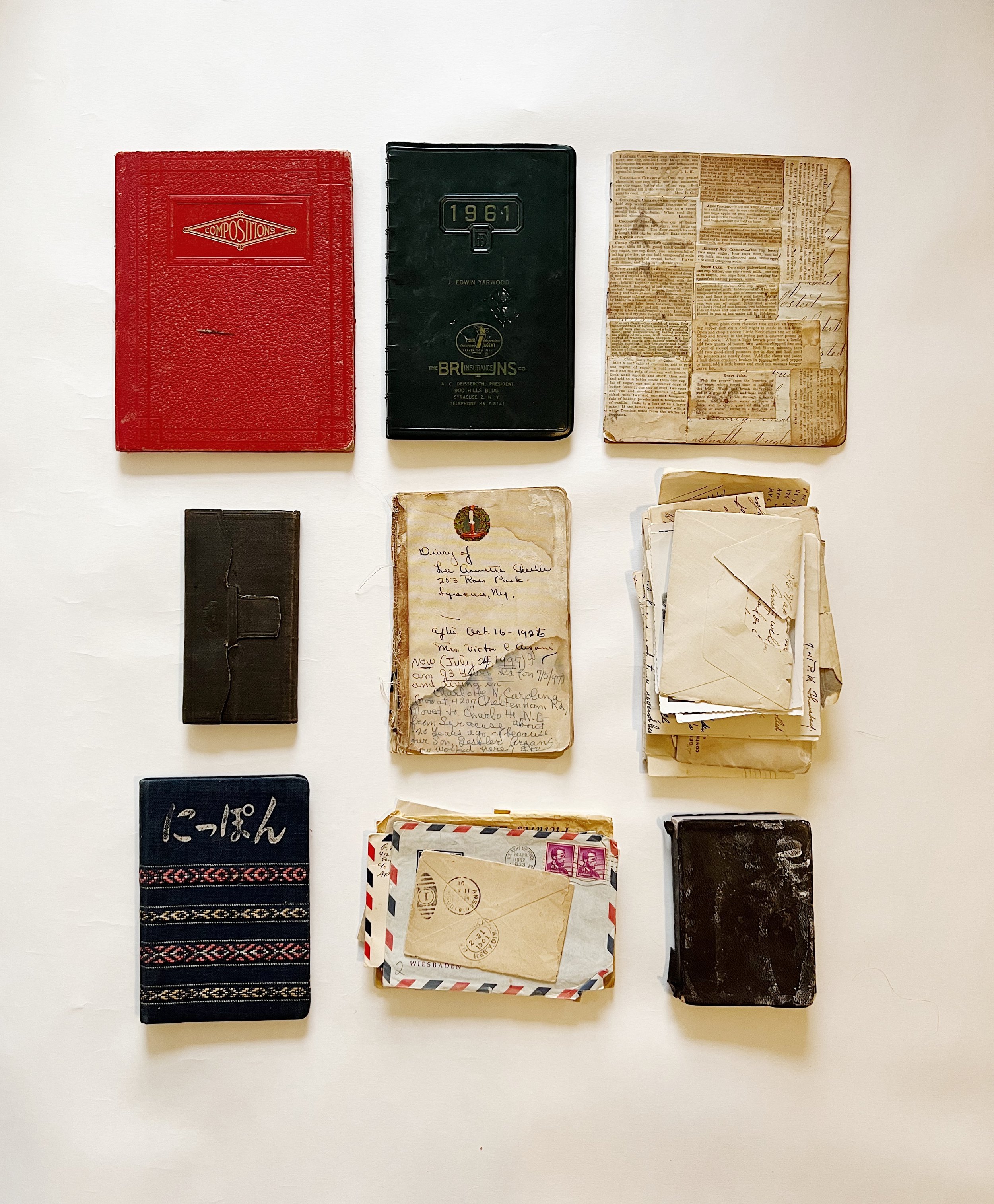

Woven in time is a pile of my great grandmother’s diaries and letters — a treasure trove I found while visiting family and cleaning out closets. Upon opening the box stashed at the back corner of a shelf, I audibly gasped out loud.

I sometimes forget that not everyone is as interested in a collection of old letters and coverless stained books. My mom isn’t —she laughed at me for getting so excited.

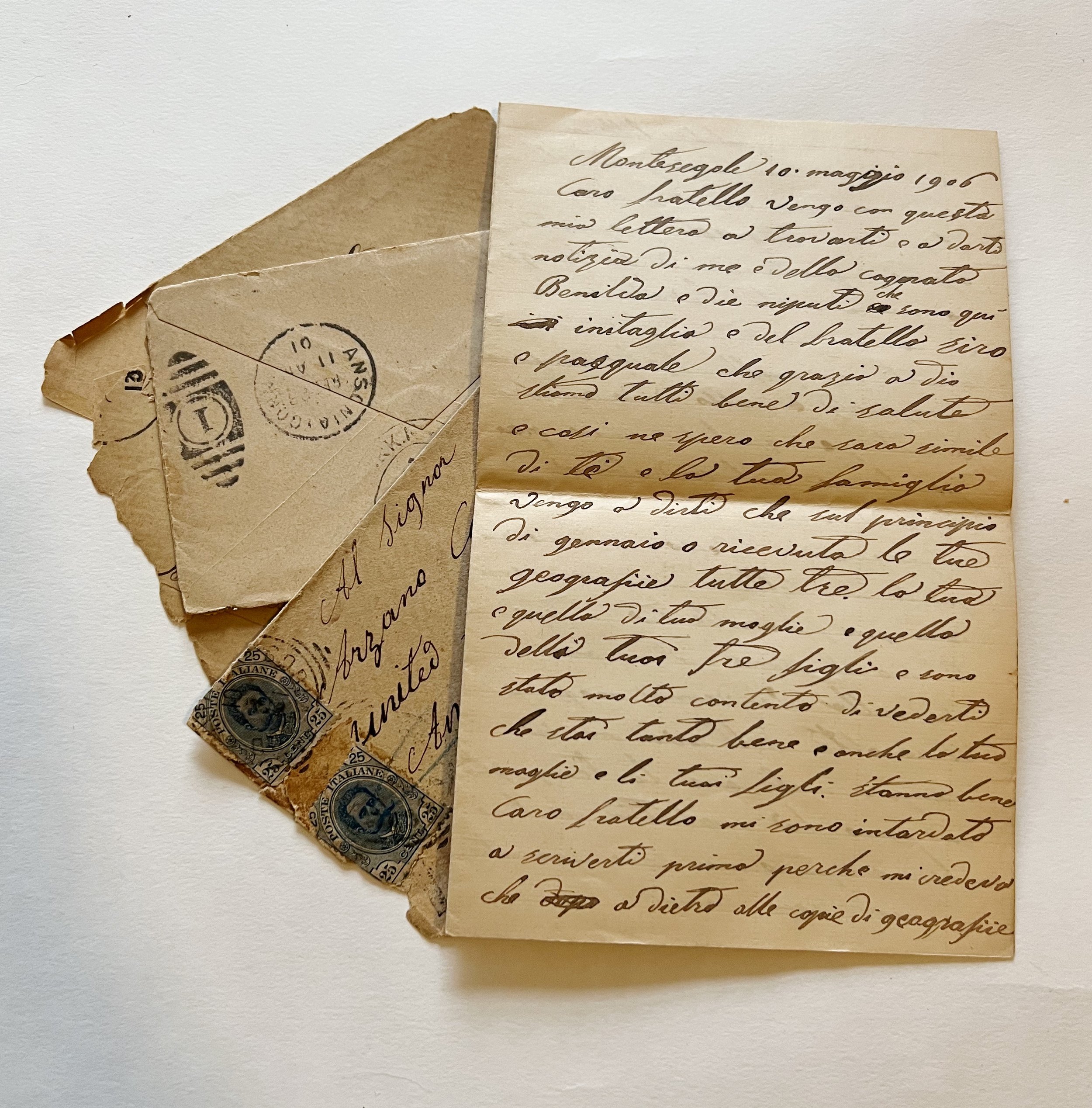

Sure, the scripted Italian letters are beautiful and the ability to read a hand typed recollection of the day my great grandmother’s father died is a pretty rare experience, but what do you do with it?

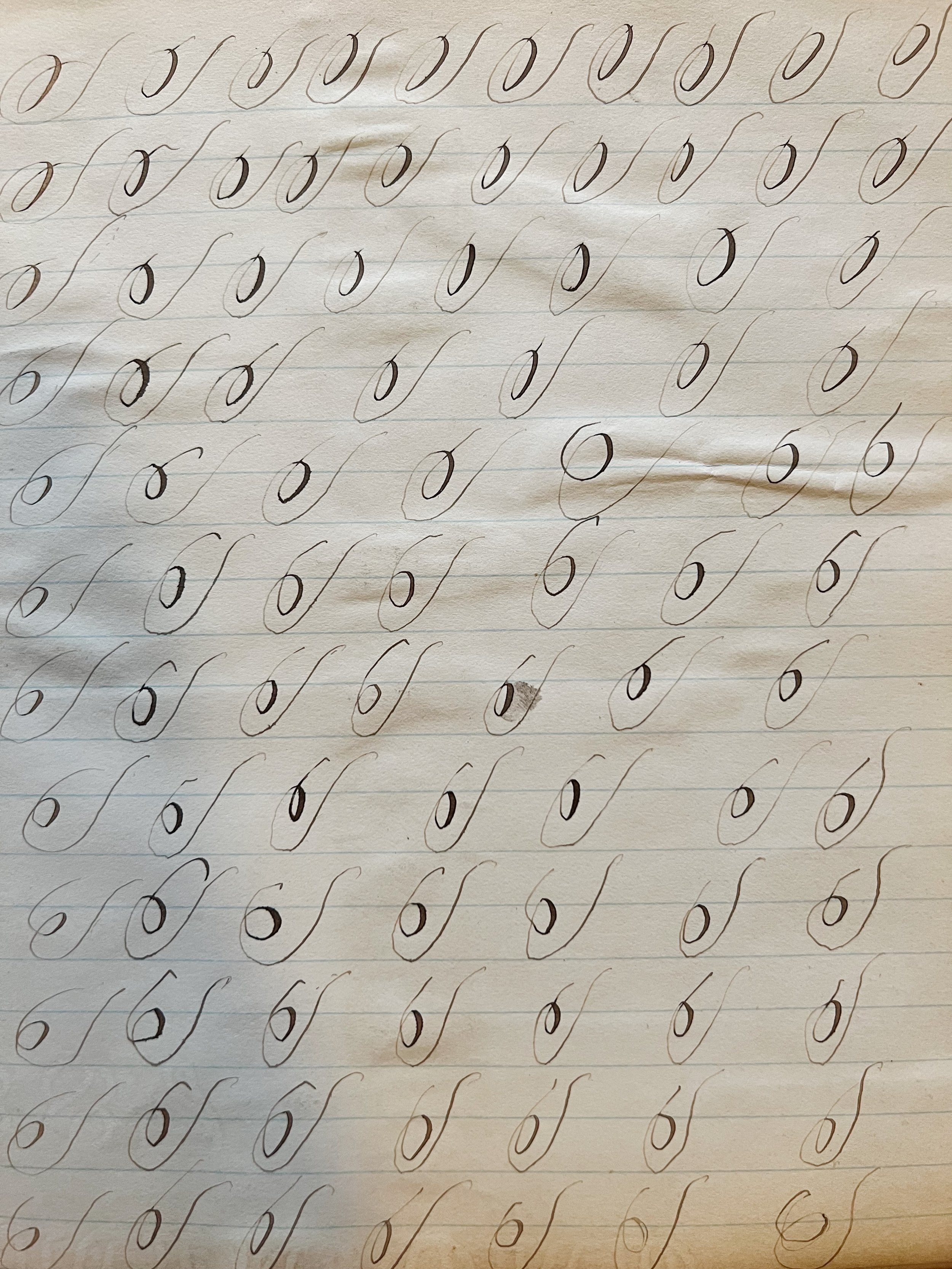

You might smirk at the odd things a 1920s diary will include: rates of postage, rate of income stocks, weather signals from the US Department of Agriculture, a what-to-do-list in case of accidents listed under the title ‘Help!’ and next to it a list of antidotes for poisons.

I assume most people would throw away something as useless as penciled key notes, by this I mean literally traced shapes of keys drawn lightly in pencil with numbered notes inside and arrows indicating things like: spare wheel.

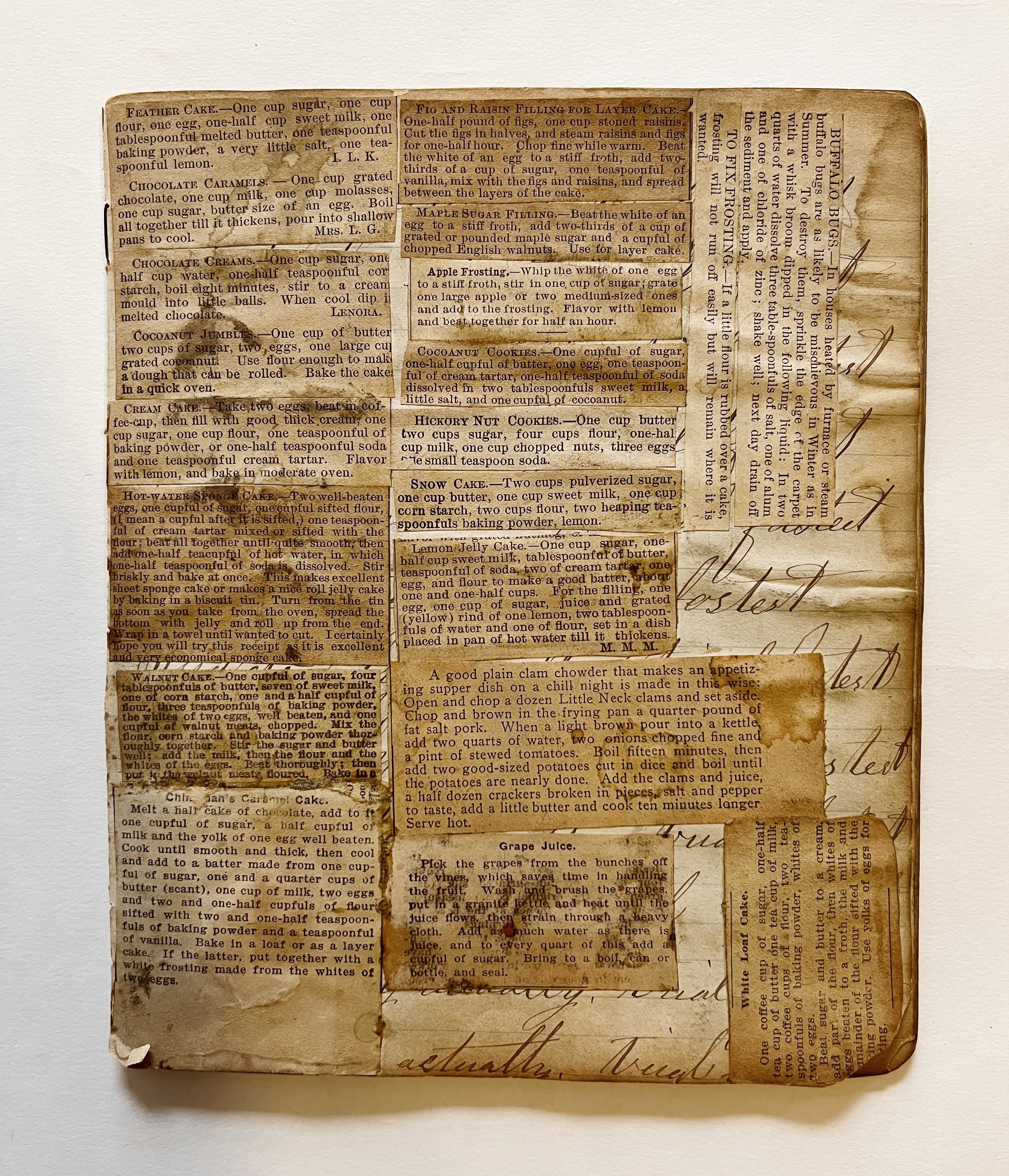

Why hold onto the collaged and now yellowed newspaper clipped recipe pages that include how to get rid of buffalo bugs pasted just above:

‘to fix frosting—if a little flour is rubbed over a cake, frosting will not run off easily but will remain where it is wanted.’

Is there any value in a handwritten mortgage ledger from the 1930s? I still don’t know what to do with this odd collection of very specific information.

In some ways it feels wrong to read (or attempt to read) these love letters and diaries and at the same time I love this porthole into the life of a women whose name I carry.

When my grandfather died and my grandmother, Mimi was cleaning and throwing out things, she gave me his old blueprints. With these items, I didn’t hesitate to cut them up and incorporate them as material in my own work. I knew right away what I wanted to do with them.

Loyal & Royal, 2013, Serigraphy, Collage, Acrylic on Paper, 30” x 44” Inches

It would have been too heartbreaking for them to sit in a corner to fade away.

While I am still trying to decide which items from my personal collections I would like to commission Nan to work with, I’m unsure whether or not I have all the answers to her questionnaire.

If you were to submit a collection commission form, how would you answer the following questions: