I’ll admit, I didn’t know there was a word for defining a collection of passages written in books, until I visited the exhibition, “Ann Hamilton: The Common SENSE,” at the University of Washington’s Henry Art Gallery.

In her own words, Hamilton reflects on the idea of “readers reading readers:”

“In silence or in speech, reading and being read to are other forms of touch. The words of poets and writers stir us. When this happens we may be compelled to note, copy or underline and often to share that touch - by passing the book from hand to hand, by reading out loud, or by sharing the page.”

Ann Hamilton quote

I could really go on and on about my personal histories of writing; collecting stories about people like I was some sort of Harriet the Spy, but I will try to stay focused. A true commonplace is not about writing and recording other people’s secrets, but rather “a notable passage in a work copied into a commonplace book.”

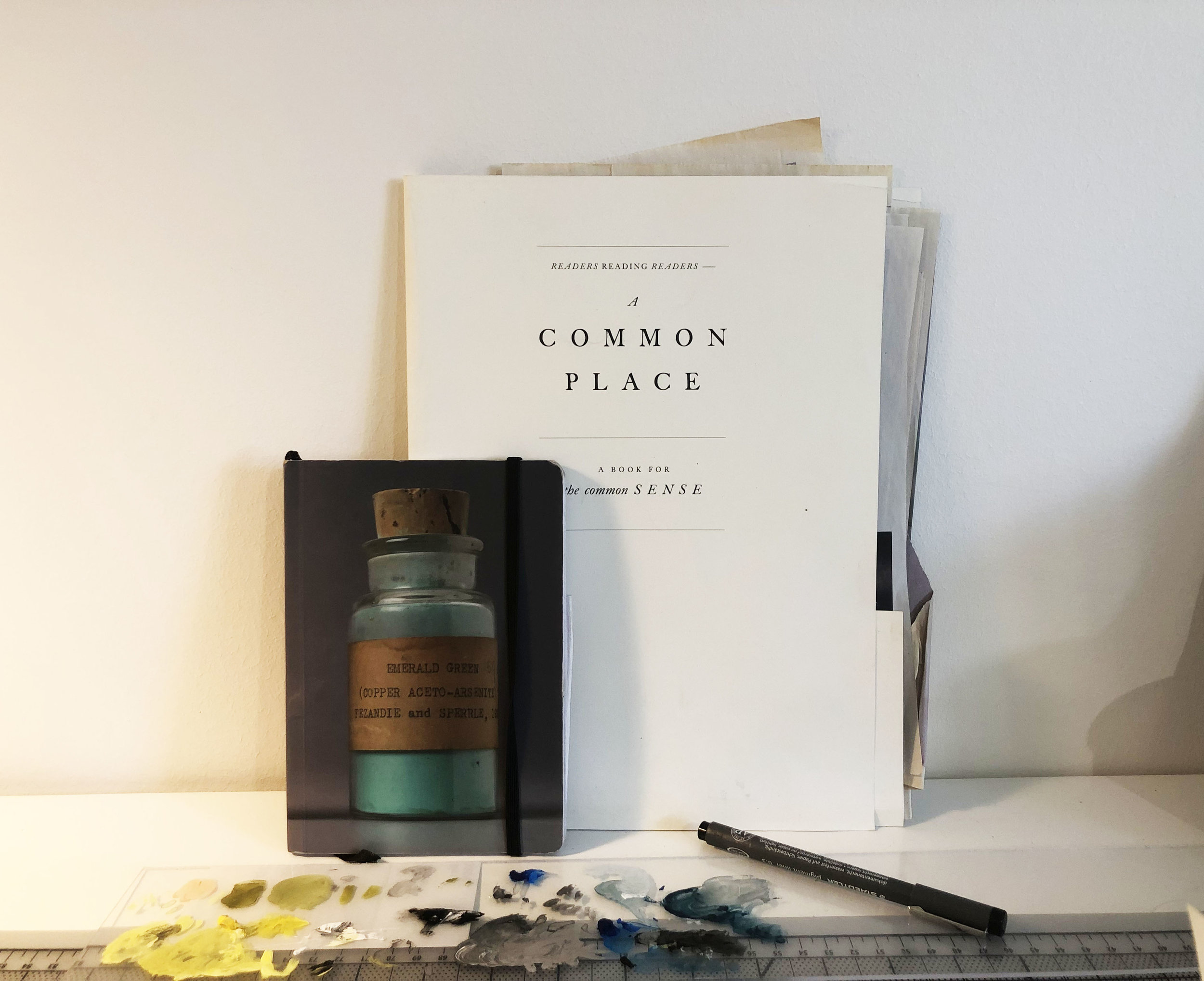

A collection of my favorite types of commonplace books

My favorite type of commonplace book is the kind that has a strap to keep your pages together, useful for when they start to become unbound. They also have one of those convenient ribbon bookmarks attached. And the really good ones have a pocket or envelope in the back, to keep important findings.

Used & Unused

I’ve been collecting and receiving pocket sized note books for as long as I can remember. The style of the book often reflects various phases in my life or places of travel. My favorites are either gifts from friends or come from places that have provided inspiration, most of which are museum gift shops featuring artwork from a select exhibition or an artist crush.

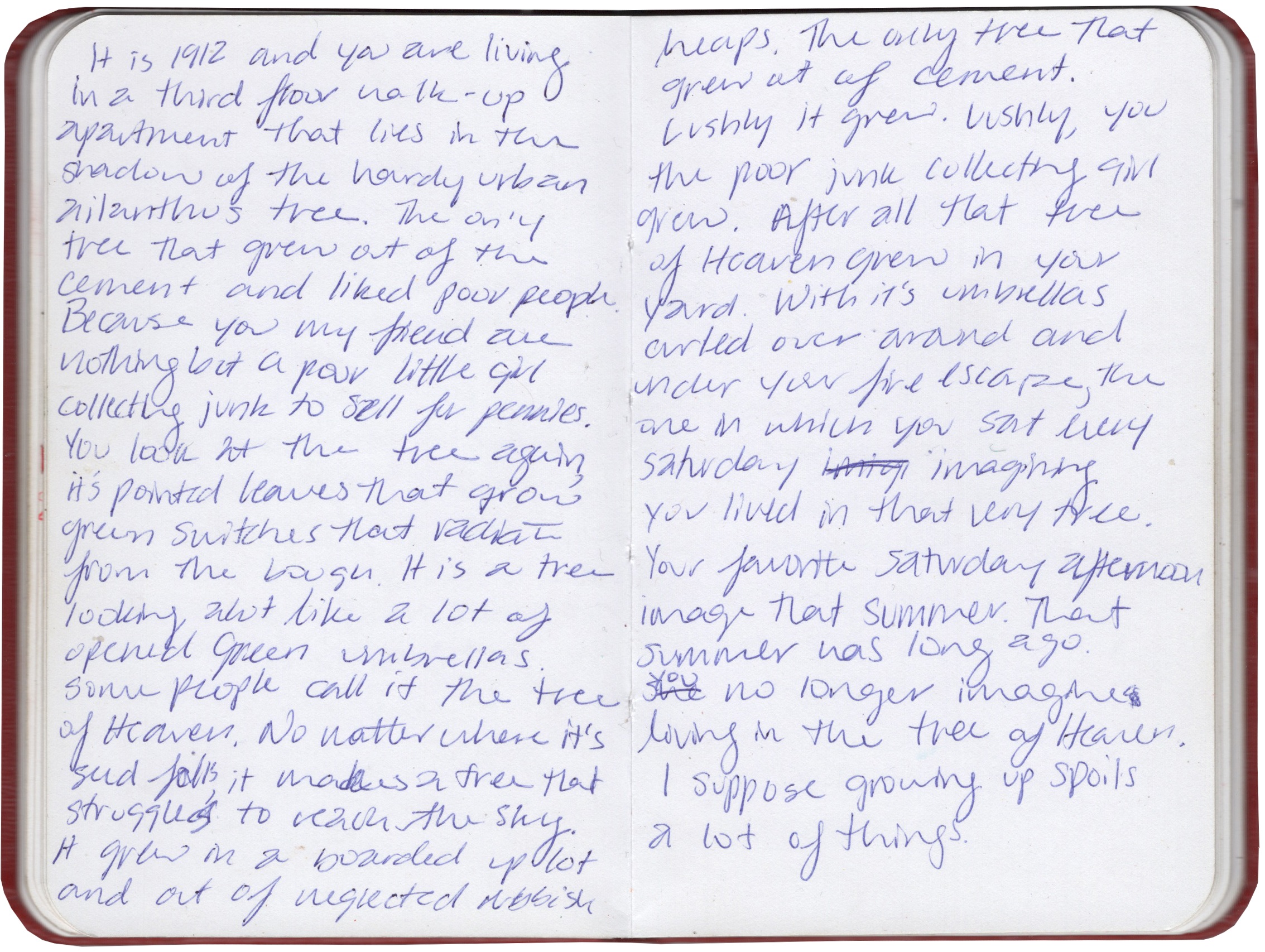

The art of scribbly handwritting

These note books are markers for pivotal passages, recounting and recording words from strangers or people of personal connections. Essentially, commonplace books are the art of list taking with influential ideas; made up of words behind bullet points, in between a lot of quotations and completed with proper citations. Add page numbers if you need to refer back to the original text. I’ve gotten better with this as I’ve gained practice.

My commonplaces often serve as sources for my artwork; from the symbolism in the slow but steady coming of age story, “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn,” to the late photographer, Diane Arbus’ accounts of visiting a nudist camp. Sometimes I stretch what defines a commonplace to words attempting to record a visual image. These can be quick notes about an idea or descriptions of a fleeing moment; photographs I didn’t take or paintings I never made.

Diane Arbus quote that inspired “Nothing But a Bandaid,” 2010, Ink & Colored Pencil on Paper

A collection of photographs I didn’t take

Some of these commonplace books recount the humorous and honest childhood tales of people who have left a lasting impact, like Ms. Virginia Short. Our unsuspecting friendship began when she was in her late 80s, working her last job, and I was in my late teens, working my first job.

Ms. Virginia’s Stories

“The Heads Don’t Match,” 2019, Acrylic & Gouache on Paper inspired by Ms. Virginia’s childhood memory of replacing broken china doll heads

I followed her around the card store, furiously writing down anything she would tell me. She was spunky and sharp with a remarkable knack for somehow being able to smile, laugh and scold simultaneously. I was too slow of a note taker and lacked her short hand talent.