Paradoxes keep reappearing, like the inconsistently consistent way I write and publish my thoughts here.

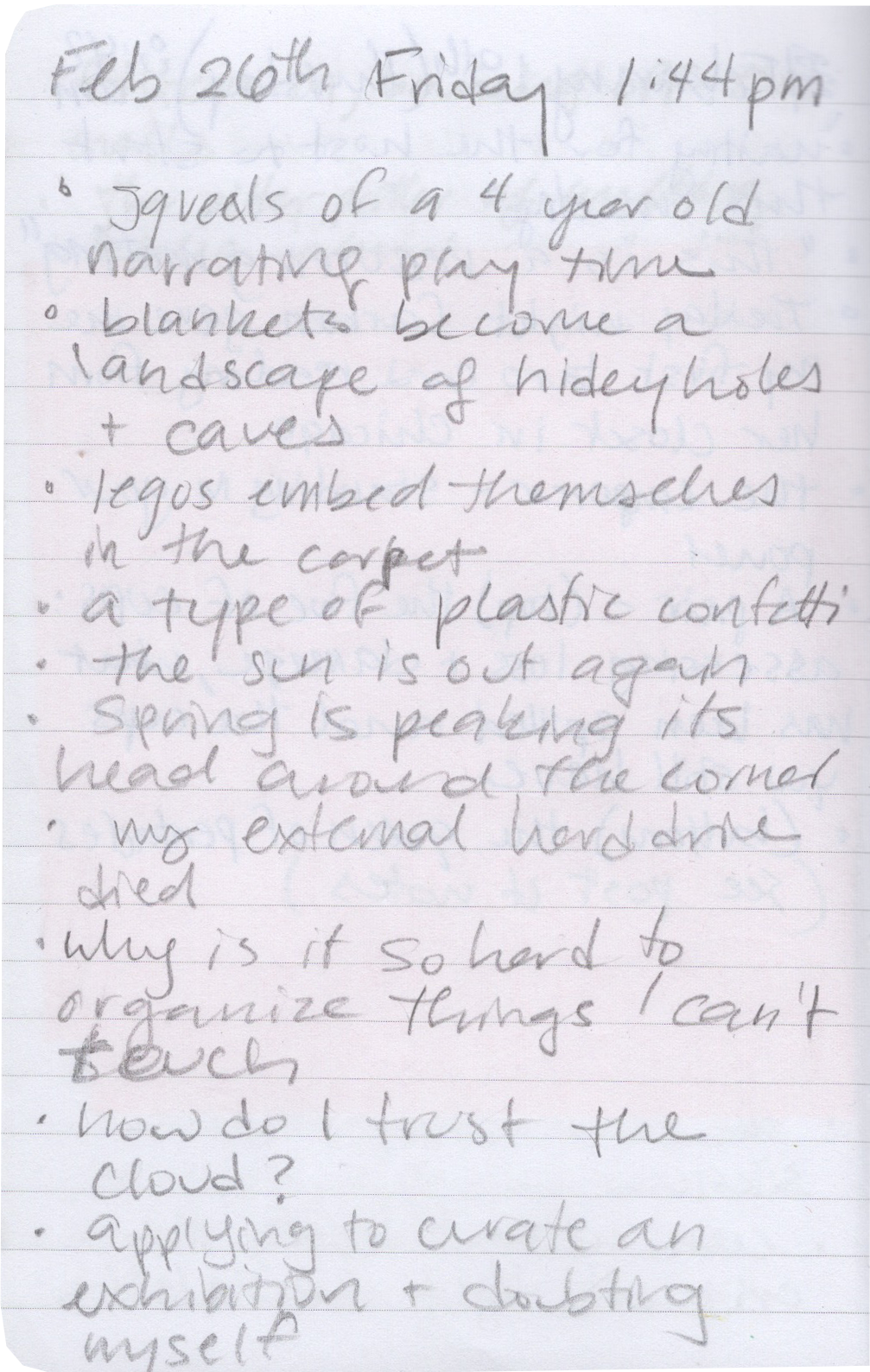

They sneak up in my everyday encounters and attempts at routines. Like my ‘daily’ (sometimes once a week or whenever I can) practice of writing lists - a whatever comes to mind, walking list.

One list came to me in the middle of the night, written on September 17th, 2020, after moving to a new city in a pandemic while also under the threat of wild fires.

It became a poem embedded in the sculpture, Stack of Words, made from a balancing act of modular components.

Something about a secret poem that couldn’t be read shelved within an absurd sculpture made of everything from: packaging cardboard to carpet padding, embroidery thread, a twig and copper wire to plaster and repurposed wood, a leaf and a rock, plaster and cement, bicycle tire tubes and a ceramic candelabra. It represented a layered complexity that words felt incapable of containing.

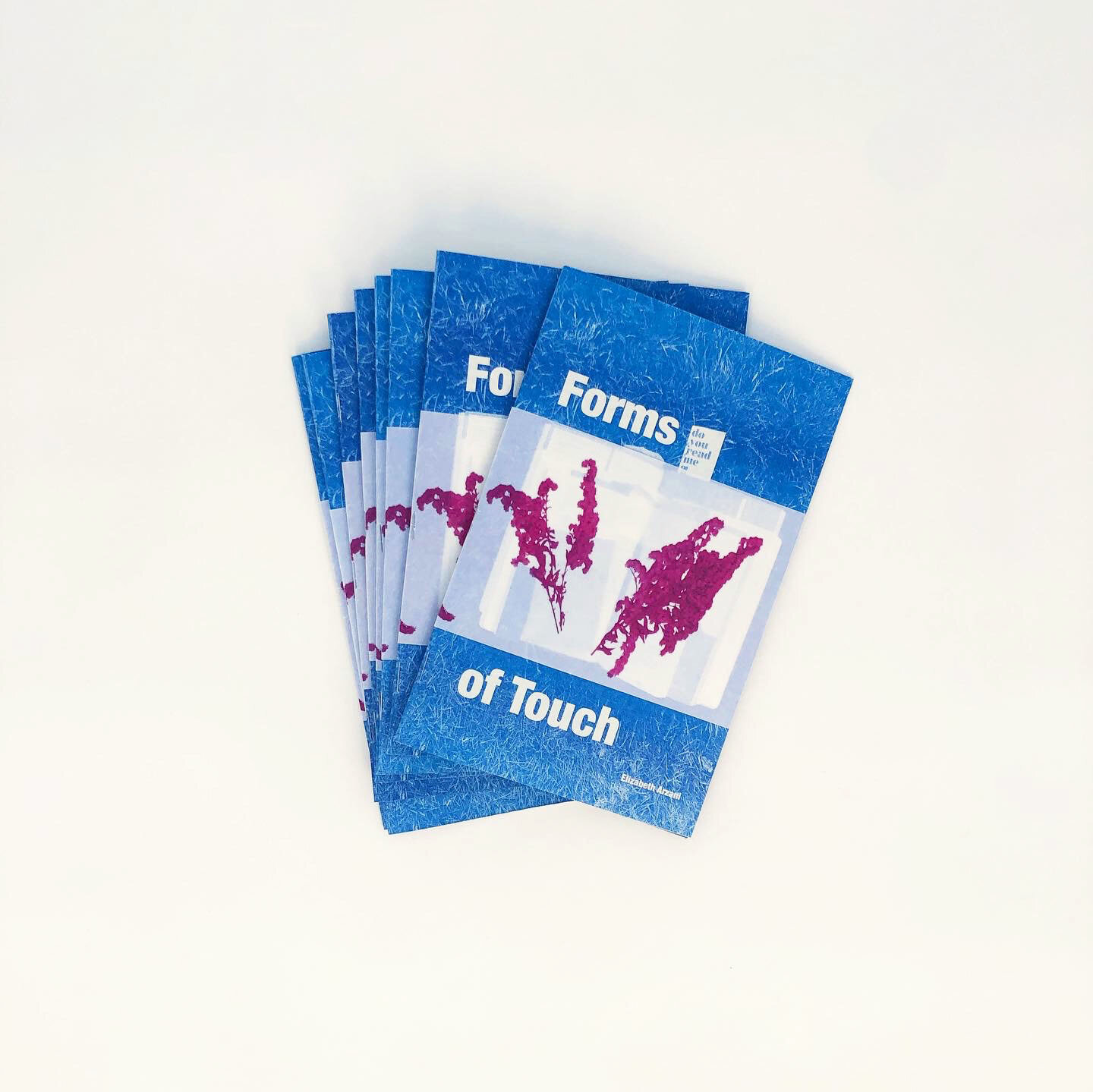

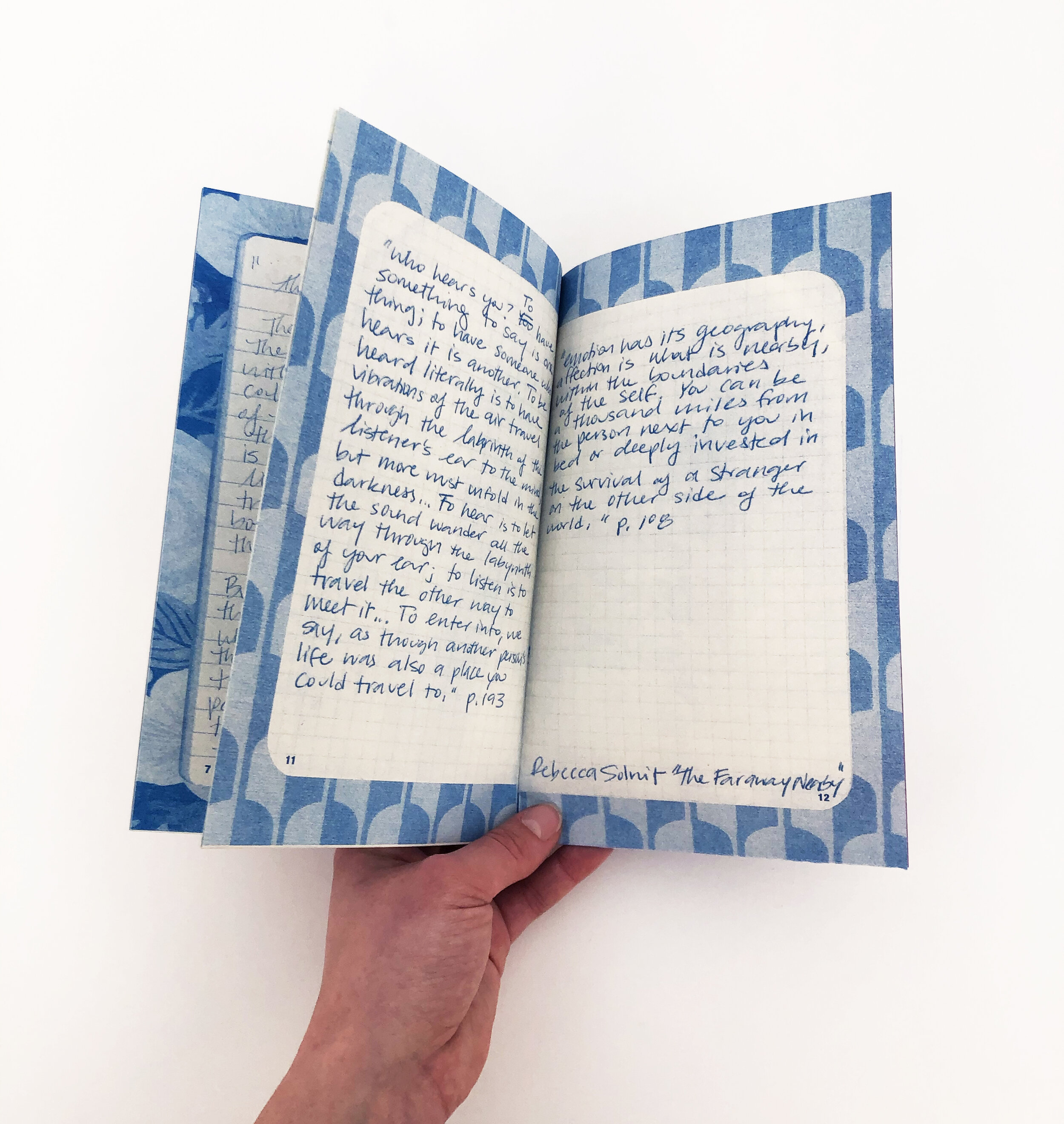

Paradoxes like ‘alone together’ emerged for many as a mantra at the beginning of the pandemic, but it was the oxymoron, ‘faraway nearby,’ the title of Rebecca Solnit’s collection of essays, which had been living with me prior.

The title itself is said by Solnit to be gleaned from the painter, Georgia O’Keefe, noting the way she signed her letters after she moved to New Mexico, although as of yet, I’ve only found a painting with this title.

Solnit’s words, ‘The Familiar Edge of the Unknown,’ became the title of my recent two-person exhibition with painter, Tanner Lind.

Video courtesy of Alan Viramontes

"The bigness of the world is redemption. Despair compresses you into a small space, and a depression is literally a hollow in the ground. To dig deeper into the self, to go underground, is sometimes necessary, but so is the other route of getting out of yourself, into the larger world, into the openness in which you need not clutch your story and your troubles so tightly to your chest. Being able to travel both ways matters, and sometimes the way back into the heart of the question begins by going outward and beyond. This is the expansiveness that sometimes comes literally in a landscape or that tugs you out of yourself in a story...just to know that the ocean went on for many thousands of miles was to know that there was an outer border to my own story, and even to human stories and that something else picked up beyond. It was the familiar edge of the unknown, forever licking at the shore."

pg.31 Rebecca Solnit, The Faraway Nearby

My individual work featured in the exhibition was about what Solnit describes as going underground, ‘the digging deep.’ I had dived head first into personal experience, private conversations and inner dialogues.

In many ways, I was referring to a category of study that the artist and writer, Moyra Davey defines as ‘the Wet.’ In her essay, The Wet and The Dry (The Social Life of the Book), ‘the Wet’ is introduced as a problem, a ‘welling up’ of something not ready to be told, what cannot be faced, the opposite of ‘the Dry.’

Installation View

This process of working is a visual language of in-betweens, similar to how Jan Verwoert defines abstraction in his essay, The Beauty and Politics of Latency: On the Work of Tomma Abts. It holds two or more things at once, what Verwoert describes as “temporal latency in twofold: that which is not yet and that which is no longer present…an echo chamber of the yet unthought and the presently forgotten.”

It is not that unlike how Davey details her ‘daily rehearsal of lost and found,’ the moments of looking for what-was and the feeling of there it is.

“The ritual is about creating a lacuna, a pocket of time into which I will disappear…Lost and found is a ritual of redemption. If I find the thing then I am a worthy person. I have been granted a reprieve…I know this ritual is a rehearsal for all the inevitable, bigger losses. I think if I can only find X, then I am holding back the floodwaters, I am in control.”

Moyra Davey, Index Cards

(Left) Why Can’t You Hear Me?, 2020, (Right) Is It You?, 2020

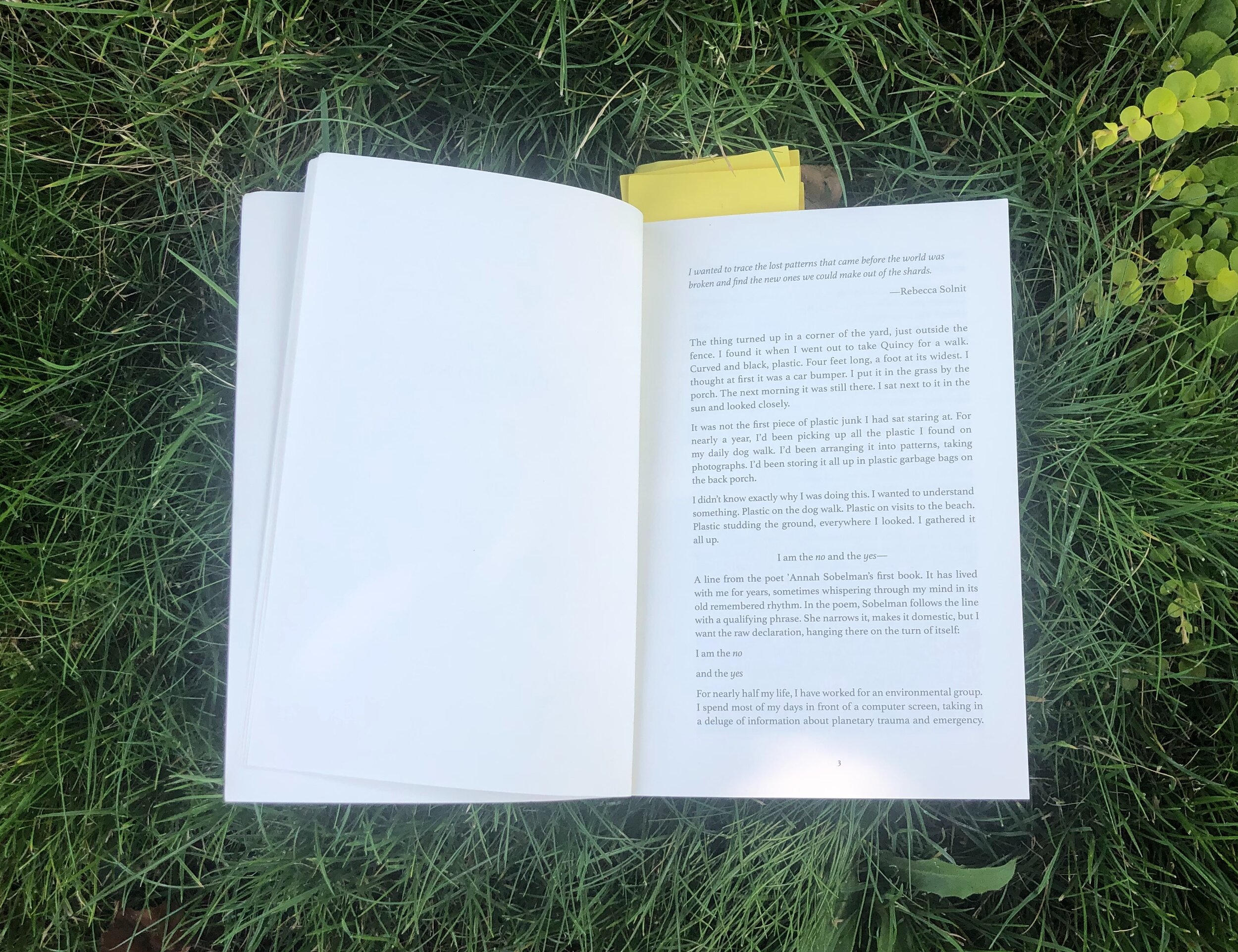

My own lost and found story occurred on a late afternoon, in the middle of summer. The branches were swaying in a welcomed breeze when I found Allison Cobb reading from her recently published book, Plastic, An Autobiography. Sitting in 1122 Outside, a backyard gallery, I listened, to her detail ‘the yes’ and ‘the no’ as a different way of saying ‘the Wet’ and ‘the Dry.’

It was my own ‘yes’ and ‘no’ that led me to accidentally, yet eagerly, join a poetry reading I didn’t know was going to happen. In a series of unfortunate events: wrong turns that I couldn’t correct until seven miles later, the spraying of sticky cold-brew coffee, fumbling the dates for hotels and arriving without a place to stay; a heat wave and an early fire season, accompanied by the hazy skies above the dry desert and the blood orange ominous sun that I’ve seen more than I’d like to. This was my no, my hell no.

The color of the sky during the fires, September 2020, Portland OR

Yet, each spill, wrong turn and incorrect combination of numbered dates are what led me to my yes. To the happenstance of sitting at a new-to-me place at the right time on the right day after driving through the night to return to where I started. The no meeting the yes.

The bizarre shift of unexpected circumstances, in under 24 hours lead me to sitting on a bench listening to Cobb read aloud.

“ I am the no and the yes - a line from the poet 'Annah Sobelman’s first book. It has lived with me for years, sometimes whispering through my mind in its old remembered rhythm.”

As I continued to read on my own, I found Cobb pulling this line along, entangled in her writing; explaining her own lived experiences and identifying them in others.

Found in both the pages of Cobb’s book as well as beside her at the backyard podium, I listened and witnessed as visual artist and third generation atomic bomb survivor, Yukiyo Kawano described how she constructs her ‘no,’ as life-sized sculptures of bombs made with her ‘yes’ - deconstructed kimonos from her grandmother, weaving them back together with her own hair.

I also learned about Eve Tuck, scholar, Unangax̂, an enrolled member of the Aleut Community of St. Paul, Alaska, and Associate Professor of Critical Race and Indigenous Studies at the University of Toronto. Tuck is identified as having a “yes that takes the no with it, desire as synonymous with life in all its contradictory, disconcerting complexity.”

“Desire, yes, accounts for the loss and despair, but also the hope, the visions, the wisdom of lived lives and communities. Desire is involved with the not yet and, at times, the not anymore…desire is about longing, about a present that is enriched by both the past and the future. It is integral to our humanness.”

I find my ceramic work to be a similar desire - an effort to encapsulate the truth of contradictions. I approach this material as a novice, asking the impossible to stand with its head held high, but instead of being disappointed by its inevitable slump and pull of gravity, I am intrigued by the attempts. These surprising moments where expectations have folded in on themself, but still stand, if only slightly; remaining as a failure to fail.